Colour and music rolled into one

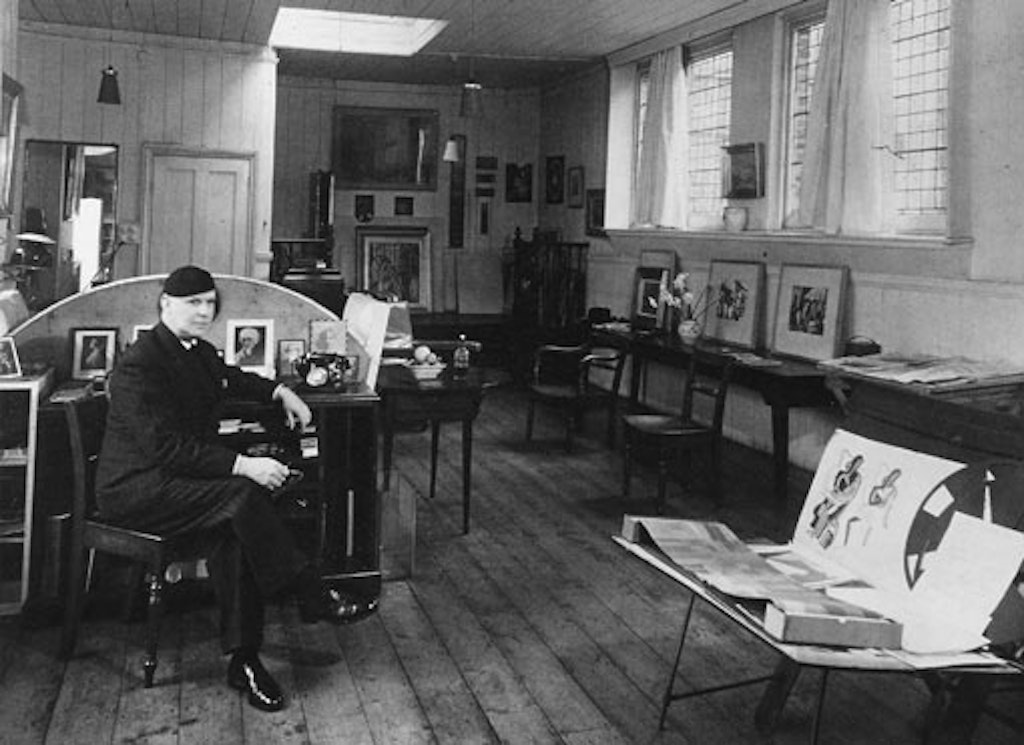

Image of Roy de Maistre in his London studio c1940, from Roy De Maistre: the English years 1930–1968 by Heather Johnson

Image of Roy de Maistre in his London studio c1940, from Roy De Maistre: the English years 1930–1968 by Heather Johnson

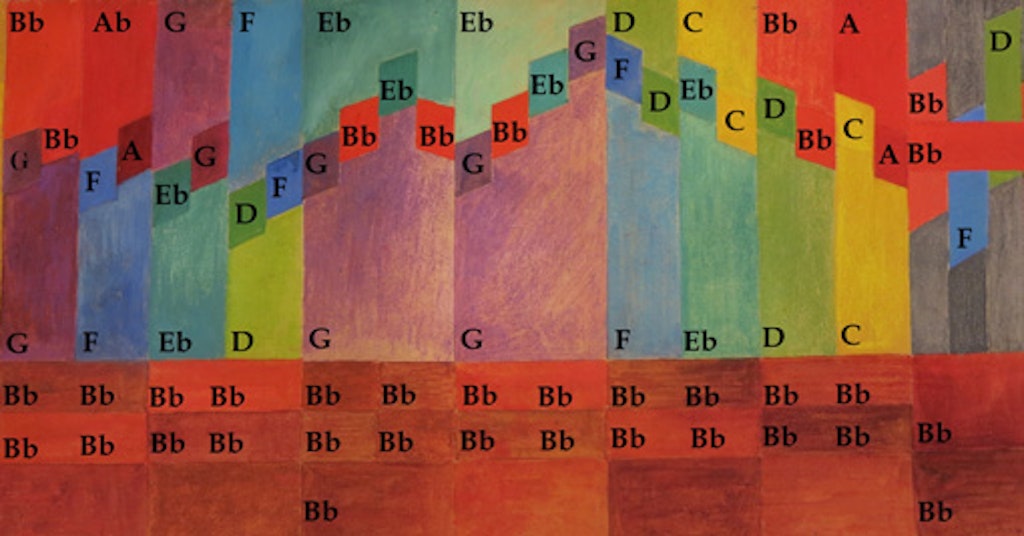

Painted across five meters of two overlaid piano rolls, Colour music c1934 by Roy de Maistre translates a classical music score into an array of vibrant colour. The work is based on a unique colour music code that de Maistre developed in the early stages of his career.

De Maistre’s passion for colour and music probably began as a student of the violin and viola at what is now the Sydney Conservatorium of Music and as a student of painting at both the Sydney Art School and NSW Royal Art Society. Together with Adrien Verbrugghen (son of Henri, the Conservatorium’s director), he was exposed to the newest trends in art and thinking, and began to develop a colour music code, building up a range of colour charts and palettes.

De Maistre’s code was based on Isaac Newton’s colour spectrum (published in Opticks in 1704). It associated the seven notes of the octave with the seven colours of the spectrum ROYGBIV (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet).

While de Maistre’s colour theories were primarily developed between 1916 and 1919, he revisited these ideas when he moved to London in the 1930s. It was at this time he created Colour music, which you can see in the right foreground of the photo above, taken in his London studio around 1940.

Carefully and methodically, de Maistre outlined the musical score in pencil, representing notes as vertical shapes, each individually coloured and then divided and subdivided – like beats of a quaver. As with a musical manuscript, the colours appear to ascend and descend the picture plane. Colour and height variations within the work appear to relate to pitch, becoming lighter for the higher notes and progressively darker for the lower and deeper notes.

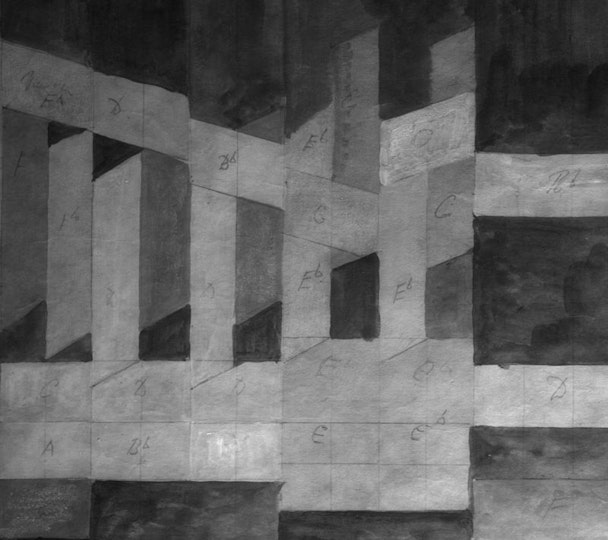

A section of Colour music annotated with the corresponding musical score

So what is the piece of music? Faint pencil inscriptions found on the roll had provided some clues, but recent investigations using infra-red reflectography supported theories by Niels Hutchinson that the score is in fact Haydn’s Trio in B Flat Major (1794 – Hoboken XV:20) for keyboard, violin and cello.

It is interesting to note that de Maistre’s biographer Heather Johnson reports that no sheet music was found in his studio after his death, suggesting he may have memorised the score by listening to it or perhaps he had the synesthetic talent he claimed.

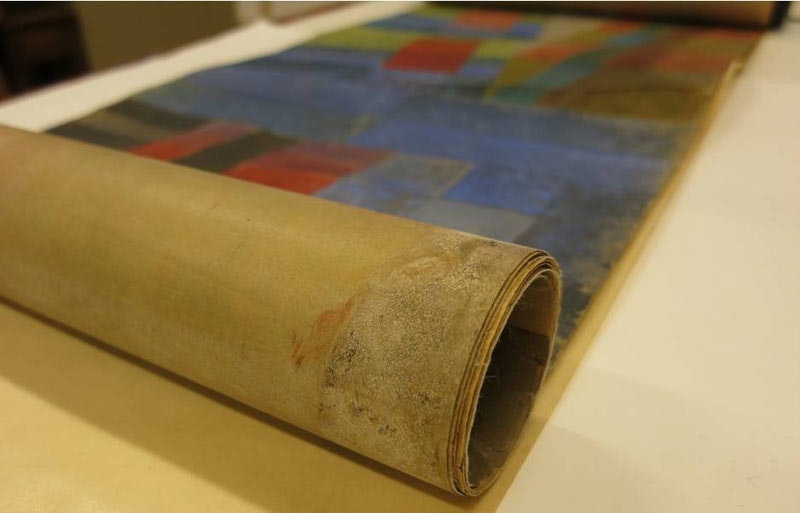

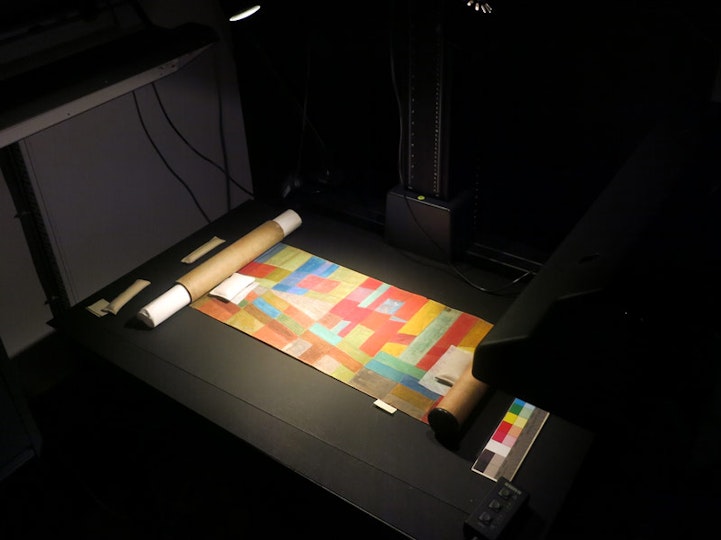

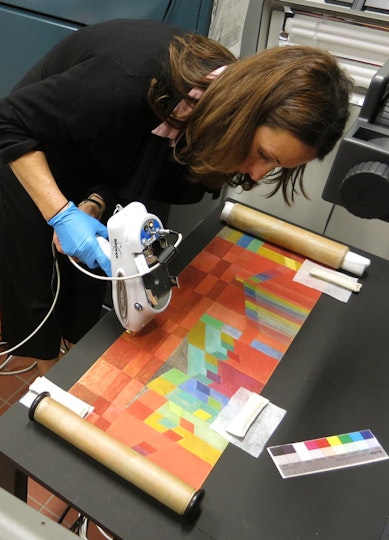

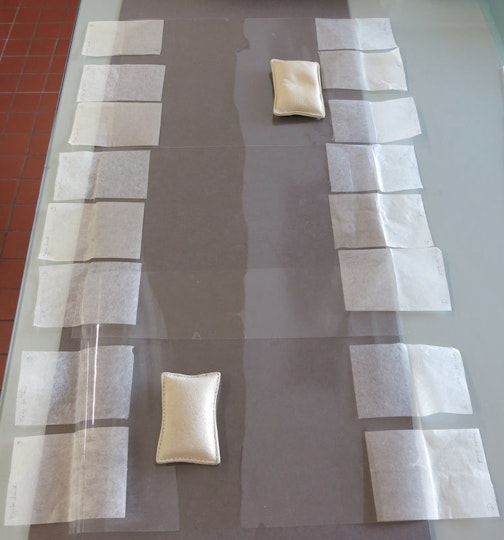

Colour music – gifted to the Gallery in 1969 by Sir John Rothenstein – has been a source of much interest to art and music historians who have come here to view it over the years. As a result, the inherent fragility of the work, primarily due to the poor quality of the paper, has meant that it has suffered severe wear and tear. Thankfully, with the assistance of funds provided by the Conservation Benefactors, the work has been recently conserved and stabilised for display in the exhibition Sydney moderns: art for a new world and for future research. Funding has also allowed for the scientific analysis of the roll, including pigment identification to provide more insight into de Maistre’s materials and techniques.

Browse the image gallery to find out more about the conservation process.

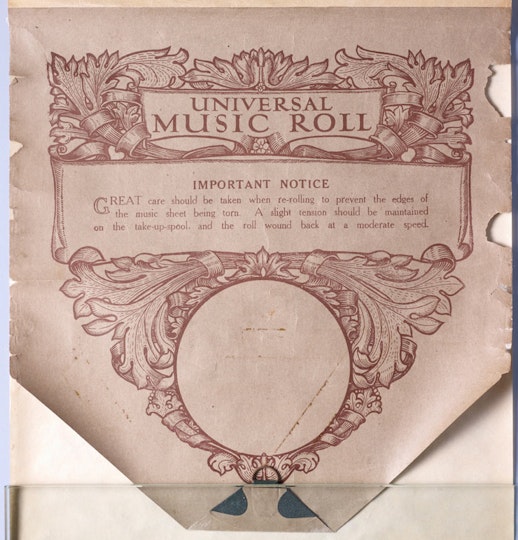

Colour music is painted on an unpunched Universal-brand piano roll, which de Maistre probably bought when he moved to London in the early 1930s. As paper production was impacted by the First World War and the Depression, paper of this period is usually poor quality and prone to discolouration.

Rolling and unrolling of the Colour music piano roll over time had resulted in significant wear and extensive tearing. In this image, several tears can be seen along the edges of the roll, most with poor-quality tape repairs, which have discoloured the paper.

Using infra-red photography, de Maistre's pencil annotations under the paint layers were revealed. This confirmed theories that the work was indeed an interpretation of Haydn’s Trio in B Flat Major.

The newly conserved artwork.