Beneath a passing shower

Arthur Streeton’s Passing shower 1937, Art Gallery of New South Wales, after conservation treatment

In 1937, the landscape painting Passing shower by Arthur Streeton was one of the works in the Wynne Prize. It was acquired by the Art Gallery of NSW in the same year, as was the Wynne winner Elioth Gruner’s Weetangera, Canberra. In the early forties both paintings were part of a four-year touring exhibition to the US and Canada. However, for the past five decades Passing shower has been in storage, unsuitable for display due to its poor condition. Conservation treatment was necessary for the painting to be exhibited again.

The treatment began with researching the painting, including its materials and (conservation) history and the techniques used by the artist. It is an important part of a conservator’s job to establish what is part of the artist’s original intent and what is not.

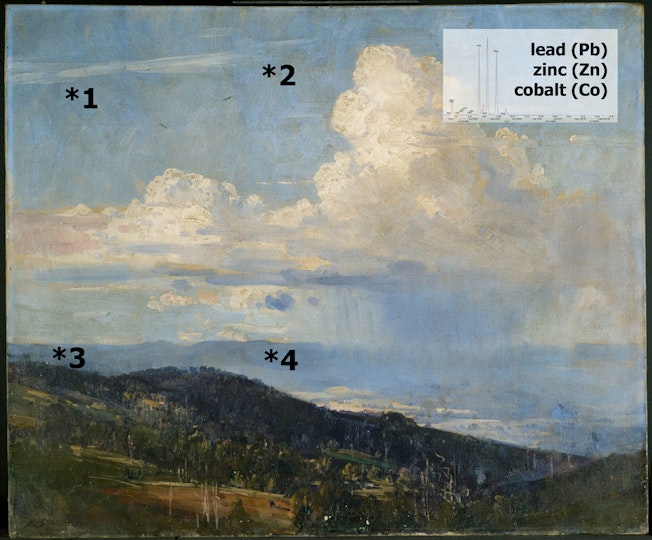

Pigments and other materials present on an artwork can be identified using special equipment and technologies. X-ray fluorescence (XRF), for example, can be used to identify specific elements, which can then be linked with art materials. In this case, we found that the paint in the sky contained lead, zinc and cobalt. This means that Streeton mixed cobalt blue with lead white and zinc white paints to create the vibrant blue colour that is so typical of the skies in his work. However, the colour of the sky in Passing shower had become obscured by dark grime and varnish layers.

Our first step was to remove the top layer – a synthetic varnish applied in the late 1950s – which improved the appearance of the artwork but did not yet reveal the vivid colours we suspected were there. A dark grime layer remained, which was not as easy to identify. Apart from the practical considerations of removing deposited material without causing any damage to the original paint layers, some ethical questions arose. When was this layer deposited on the surface? Was it something that Streeton himself applied? Could it be intentional?

Knowing that the painting had been treated in the fifties, it is very unlikely that the material on the surface was applied by Streeton and had remained there ever since. Also, it is unlikely that the painting appeared as uneven and dark immediately after it was created. On 8 April 1937, the Sydney Morning Herald observed:

In ‘Passing shower’ the artist has cunningly but not too obviously, stressed a shadow near the eye, in order to give misty softness to the pale curtain of rain which hangs over the valley beyond.

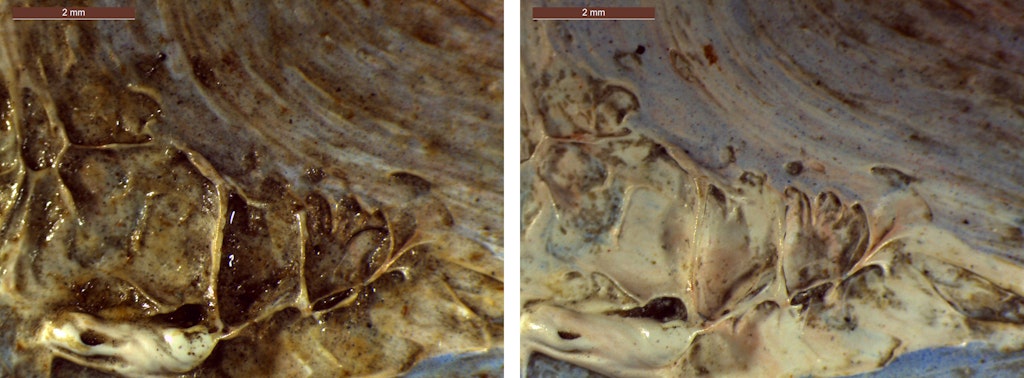

A stereo-microscope was used to monitor the conservation treatment

However, to the modern eye, this subtleness of technique was not visible at all due to the grime layer. Close examination of the surface and small tests to remove the material showed that the paint layer underneath was in beautiful condition and must have been completely dry when the dirt was deposited. We therefore made the decision to remove the material, involving the application of a gelled solvent system, which was left for five minutes then removed using cotton swabs and de-ionised water. This part of the treatment took several weeks and was carried out using a stereo-microscope to closely monitor the process. The result was that the painting reclaimed its original intense brightness.

The treatment was completed by filling and retouching the minor losses in the foreground of the painting. Because Streeton himself probably never applied a varnish layer, we decided to keep the surface unvarnished to stay close to his artistic intentions.

Stereo-microscopic images showing the white impasto of a cloud before (left) and after (right) the removal of the grime layer

The frame for Passing shower – likely the original – also required treatment. Made in the 1930s by the renowned workshop of John Thallon in Melbourne, Victoria, it is Louis XIV-revival in style with corner cartouches, strapwork and floral ornaments on a cross-hatched background. It had been finished with brass-leaf gold imitation (also called Dutch gold or schlagmetal), as indicated by the brown corrosion spots that had appeared on the surface. The Gallery’s head of frames conservation, Margaret Sawicki, carried out the treatment, which included securing the framer labels on the back, cleaning the surface, infilling losses and minor retouching of discolorations.

The restored painting and frame will be included in a major exhibition to be announced later this year. The 2019 Wynne Prize finalists are on display at the Gallery until 8 September 2019 as part of the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes exhibition.

You can browse an image gallery of the conservation process.