Advice from the Palace Museum

Kerry Head, Art Gallery of NSW objects conservator, and Yin Cao, the Gallery’s curator of Chinese art, during the online meeting with Palace Museum staff

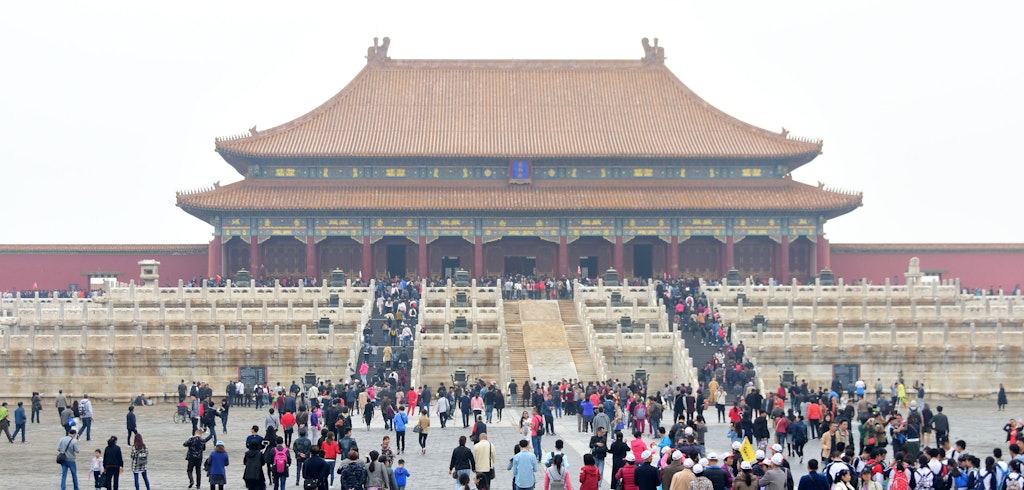

At the centre of Beijing stands the imperial palace of the Ming and Qing dynasties, also known as the Forbidden City. Today, it houses China’s Palace Museum, which has a ‘Relics Hospital’. This state-of-the-art complex, covering more than 13,000 square metres, is staffed by a large team of ‘doctors’, as they’re widely called.

These conservation experts are tasked with maintaining the health of over 1.8 million cultural objects in the museum’s collection and ensuring their longevity, using a combination of contemporary technology and traditional techniques.

Recently, senior practitioners from the Palace Museum shared some of their wealth of knowledge with staff from the Art Gallery of NSW using the technology that has transformed so many of our lives over the past year: the online video meeting.

Palace Museum, Beijing

This was an opportunity for us to draw on their scientific expertise and years of professional practice in two particular specialist areas – lacquerware and textiles – by discussing two examples from the Art Gallery of NSW’s Asian collection.

The first is a covered box with a geometric motif which is commonly known as ruyi (as you wish) cloud, made from red lacquer by an unknown artist in China during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The second is a rank badge for a third-rank civil official, featuring a rooster motif, made from silk and cotton by an unknown artist in Viet Nam during the 1800s.

Both of these objects were suffering the kinds of damage that occur through the natural ageing of the materials from which they were made, the effects of the natural environment (such as light, temperature and relative humidity) and their previous use as functional objects in daily life. In addition, there were the attempts at repair of damage that had been made by previous owners of both objects.

![[w:6956.53[Covered box]], Ming dynasty 1368-1644, Art Gallery of New South Wales](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1626345544-6956-53510px.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

Covered box, Ming dynasty 1368-1644, Art Gallery of New South Wales

For comparison, the Palace Museum staff provided case studies of objects in their collection with similar types of damage.

The Palace Museum had used a combination of analytical methods (CT scanning, Py-GC/MS Pyrolysis-gas chromatography, mass spectrometry and microscopic analysis) to gather extensive information about the original construction methods and the physical damage of their case-study lacquer object.

The analysis revealed that the object’s complex vase shape was formed from a base of solid wood followed by a series of graduated rings made from thin layers of bent wood glued together with natural protein-based glues. Over these had been applied layers of cloth and of ground clay followed by over 90 layers of lacquer. The composition of these lacquer layers was identified, which included coloured pigments, oils, waxes and natural lacquer made from the sap of the plant Toxicodendron vernicifluum.

Most people are allergic to this sap so working with the raw ingredients and the dust from sanding layers of lacquer is likely to lead to inflamed and very itchy skin, which makes working with lacquer a labour of love – or necessity!

The Art Gallery of NSW does not have either the degree of technical expertise or the scientific equipment for similar types of analysis or extensive treatments of lacquerware. However, the discussion highlighted other methods of physical repair of delicate surfaces which could be modified to fit the range of materials available in Australia.

For example, in the treatment of the Gallery’s lacquer container, methods of gentle humidification of exposed wooden support could be tested to bring misaligned surfaces back into alignment, where they can then be adhered with either a protein-based adhesive (similar to the original material used) or a synthetic substitute.

When it came to textiles, the discussions reinforced the similarities in our approaches to fragile textiles that are suffering physical deterioration because of the dyes that were used and natural ageing processes.

Similar textile case studies from the Palace Museum included the silk lining of a wooden lantern and a large velvet wall hanging. Due to the works’ fragility, methods of storage and display had been devised that allow researchers and curators to observe these objects closely without causing further damage through movement.

Our approaches to aged textiles were similar too: previous repairs are assessed for their historic value and whether they are causing irreversible damage before any treatment is commenced.

Discussions then moved on to consider various methods of removal and how to support subsequent areas of weakness.

In the case of the Gallery’s textile example – the rank badge – due to structural weakness, a preventive conservation approach will be followed whereby the exposed rear surfaces will be supported and protected with a transparent silk lining, which will allow the historic repairs to be seen. To mitigate any physical damage through abrasion of the fibres, the textile will always be supported when on display or in storage by resting it on an archival handling board.

Front of Rank badge for a 3rd rank civil official - rooster 1800s, Art Gallery of New South Wales, and the back, showing previous repairs and areas of loss and weakness

Our conversation with the Palace Museum also provided an opportunity to find out more about the history and manufacture of metal threads, including the types encountered in the museum’s textiles. Metal threads are used widely in Asian textiles such as rank badges, robes, wall hangings and ceremonial cloths.

The museum provided information about historic family-run factories which still manufacture metal threads in areas near coastal ports in China. Further research into the trading of supplies from these factories to other South East Asian ports may highlight the distribution of supplies and wider usage of these threads through the archipelago of Indonesia.

Originally, this professional exchange with our Palace Museum colleagues had been planned to happen in person, until the global COVID-19 pandemic intervened. While nothing will replace the experience of dealing with the physical object, the unexpected pivot online introduced us not only to each other but to a way in which information may be shared on a wider range of conservation treatments in the future.

Participants in this event included, from the Palace Museum, Dr Lei Yong and Dr Qu Liang (deputy directors, the Conservation Department), Dr Chen Yang (head of textile workshop) and Dr Min Junrong (head of lacquerware and jewel inlay workshop) and, from the Art Gallery of NSW, Carolyn Murphy (head of conservation), Kerry Head (senior objects conservator) and Yin Cao (curator of Chinese art), with introductions by Zhao Guoying, deputy director of the Palace Museum and Dr Michael Brand, director of the Art Gallery of NSW. The event was sponsored by the Bank of China, the Gallery’s Asian art conservation partners.