A curve is a broken line

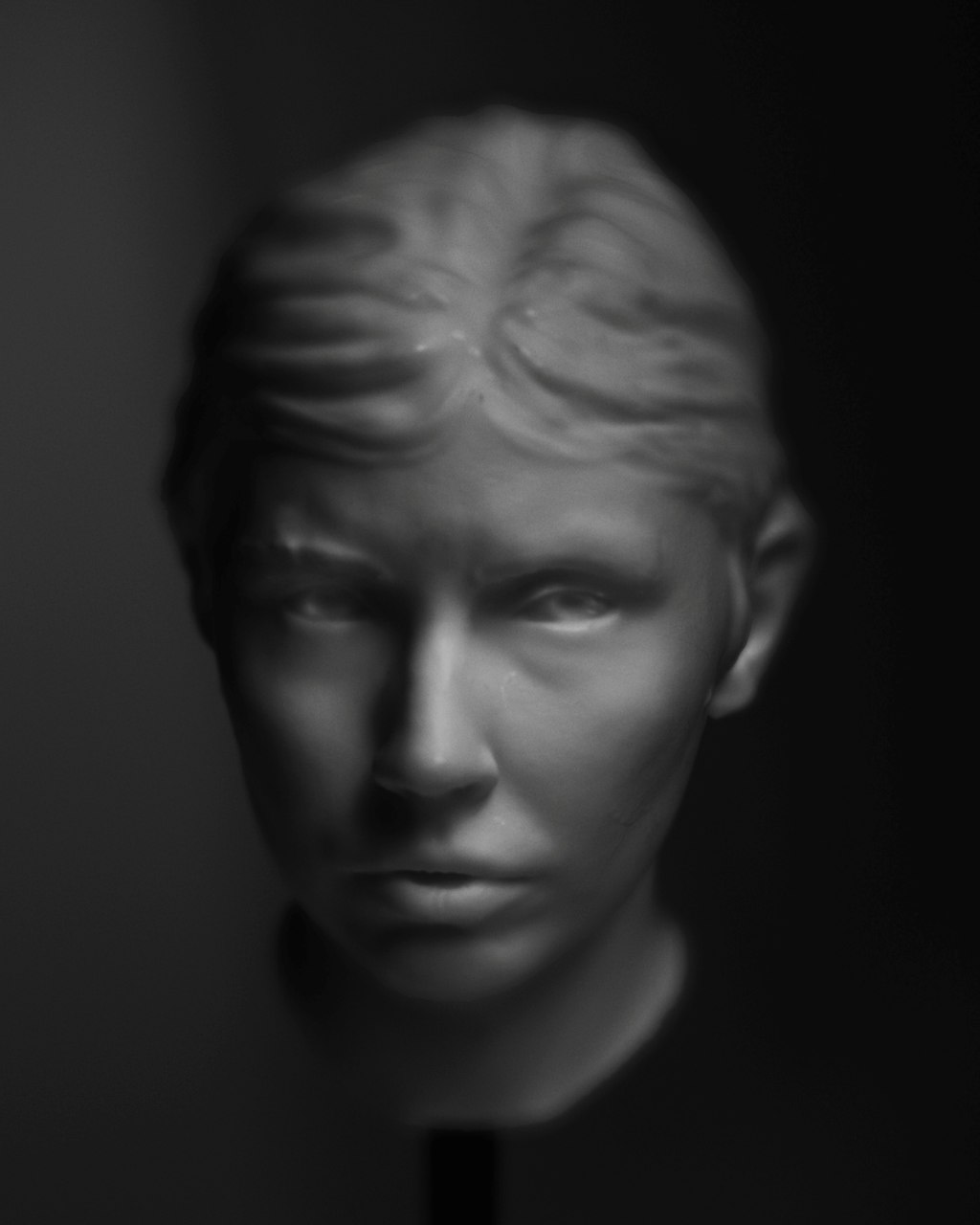

Hoda Afshar Untitled #6 from the series Speak the wind 2015–22 © Hoda Afshar

From 2 September 2023, a major solo exhibition of Iranian–Australian artist Hoda Afshar will be on display at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Hoda Afshar: A Curve is a Broken Line is an attempt to take stock, to pause and recognise the significance of Afshar’s approach to the photographic medium. ‘A curve is a broken line’, a phrase inspired by and adapted from a line in a poem by Kaveh Akbar, is an admission of vulnerability but also strength. Afshar’s photographs and videos do not sit outside the world they depict but are emotionally embroiled in it. And that very fact makes a survey of her work both poignant and timely.

Before she became a photographer, Hoda Afshar wanted to be an actress. She had applied to study theatre at the Azad University of Art and Architecture in Tehran, Iran, but was accepted into the photography course, her second preference. Once Afshar started her degree, her fascination with the theatre didn’t dissipate. She spent a lot of time with her friends in the drama department, photographing them rehearsing, on stage and off duty. She was interested in the possibilities of performance, in the crafting of characters and of fictive realities. And yet, she was majoring in documentary photography, the ostensible antithesis of the theatre.

Documentary photography is sold to us as a form of truth-telling. The documentary photographer bears witness and exposes, reporting on the world as it is, unaltered. Or so we’re led to believe. The documentary photographer doesn’t stage their shots. They ‘capture’ them. One of Afshar’s early assignments was to board a bus, with a camera concealed in her jacket, and photograph the other passengers without their knowledge. ‘Click and run’ was the directive, she tells me. The images were to be as close to ‘reality’ as possible.

One of her earliest bodies of work, Scene, made around this time in 2004–05, resembles a collection of impromptu snapshots. These images are documentary fragments, remnants of a series of underground, and illegal, parties in Tehran. At least they appear to be. The photographs were in fact staged: the parties were real, but the interactions and the gestures were made – performed – for the camera.

Afshar’s photographs of young people dancing, smoking and kissing were profoundly subversive. Both the photographer and her subjects risked arrest if the images ever circulated publicly in Iran. Why stage them, then? In photographing her friends in such a high-risk context, Afshar wanted to make sure they had agency. That they shared in the control over the image-making. Afshar calls them, to this day, her collaborators.

Hoda Afshar Untitled #7 from the series Behold 2016 © Hoda Afshar

This is a term Afshar continues to apply to the people who appear in her work. Since the beginning, she has sought to mitigate and equalise the power dynamic that exists between photographer and photographed – a dynamic that privileges the one holding the camera. The documentary photographer is often thought to be impartial and objective, but all photographers make choices. Those ‘impartial observers’ of years past, overwhelmingly white men, have defined how history is recorded and remembered, and whose stories are told, and how. Documentary photography has long been bound up in histories of exploitation and Afshar is all too aware of this fact. This is why she involves her subjects in the act of imaging them. Why she asks how they would like to be photographed. And it is also why she is still preoccupied with the tension and interplay between the staged and the unscripted image.

In 2007 Afshar relocated to Australia, where she continued her studies at the University of Technology and Meadowbank TAFE College in Sydney, eventually completing her PhD at Curtin University in Perth. When she first arrived, she encountered what she refers to as a ‘crisis’ in her artmaking. Her photographic work until this point had been closely in step with the people and the world around her, but Australia was not a place she knew. How was she to proceed with ‘documenting’ a reality when she wasn’t familiar with its rhythms or its history? In this context, Afshar became increasingly curious about the function of photographic images and how we all use them to anchor our sense of belonging and to narrate our experiences.

Now, more than ever, photographs condition how we navigate the world around us. The images we receive, swarming our media in their millions and the images we ourselves create, can define our communities. They can influence how we place ourselves in an ever-shifting network of relations and negotiate a world that is always in flux. Photographs can withstand, and aid, such complex relational dynamics because they themselves are malleable.

Hoda Afshar Limit 2014 from the series In the exodus, I love you more 2014–ongoing © Hoda Afshar

We witness the way Afshar uses photography to expose the complexity and multiplicity in the stories we are told in the series In the exodus, I love you more 2014–ongoing, which opens the Art Gallery’s exhibition of her work. This series is a case study of displacement. Returning to Iran several years after relocating to Australia, Afshar was confronted with the familiar made suddenly unfamiliar. Using the camera to mediate this dual state, she produced images that are intentionally hard to read. Objects are covered in cloth; landscapes are obscured by fog. The series considers how we use images to account for our own histories and acknowledges the way photographs can create fictions.

Following this keenly personal project, Afshar began to turn her attention outwards to address the medium’s capacity to assert a political agenda and make visible acts of violence usually hidden from view. Around 2018, Afshar started to work with video alongside photography, further amplifying the narrative intent of her image-making and arriving at an understanding of film and photography as an act of service, not simply self-expression.

Hoda Afshar Behrouz Boochani – Manus Island from the series Remain 2018 © Hoda Afshar

Hoda Afshar Behrouz Boochani – Manus Island from the series Remain 2018 © Hoda Afshar

Behold 2016, a purely photographic series, was made in a bathhouse in an unnamed Iranian location, frequented by a group of gay men who invited Afshar to photograph them and the intimate space they had created against an ever-present threat of persecution.

Remain 2018, a video and suite of photographs, was made on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, with a group of asylum seekers who remained detained as stateless men after Australia closed its immigration detention centre in 2017 and relocated them to other facilities. The idyllic landscape shocks as a backdrop to the horrific recollections of the men, recounted in haunting voice-overs, of their time in detention at the hands of the Australian Government.

Agonistes 2020 was made in a photo studio filled with 110 cameras, in which a group of whistleblowers – each of whom has exposed the wrongdoings of an Australian institution – submitted to intense surveillance by Afshar as she created portraits in the round using 3D-printing technology. In the video component of this series, they each speak of the injustices they have witnessed.

Hoda Afshar Portrait #7 2020 from the series Agonistes 2020 © Hoda Afshar

Hoda Afshar Portrait #7 2020 from the series Agonistes 2020 © Hoda Afshar

Just like the partygoers of Afshar’s earlier photographs, the subjects of these works are aware they’re being documented and often participate in the scene-setting. They are conscious of, and contribute to, the way Afshar devises and develops an image. She purposely affords visibility and self-determination to people for whom these rights have been denied. This is what defines the propulsive ambition of her practice and the indelible power of her work.

Between 2015 and 2022, Afshar developed a major body of work that has since been exhibited in parts and published by MACK as a photobook. Speak the wind is the culmination of many visits to the islands of the Strait of Hormuz, off the southern coast of Iran. There, the wind, the Zār, is thought to be capable of possessing people, inducing illness or disease. Those possessed are exorcised through ceremonies that seek to placate the wind. We are only afforded glimpses of these customs and the surreal landscape of the islands, shaped by gales. There is an intimacy we can parse between Afshar and the people in these photographs. The work is personal, but there is a politics here too. Obliquely and through insinuation, the project grapples with the legacies of the Arab slave trade. It is thought that these beliefs about the wind were inherited from those brought to Iran from Africa to be sold as slaves, a history that is, like the wind itself, a spectral presence in the work.

Here, as elsewhere, Afshar forces us to contend with violence and brutality not through blunt imagery but through evocation; through metaphor and affect, but also the embodied presence of the collaborative subject. Her work trades in truthtelling, but not in the way of straight documentary photography or reportage. There is a lyricism here that does not dilute the political charge of her practice, but instead amplifies it.

Hoda Afshar Untitled #11 from the series Speak the wind 2015–22 © Hoda Afshar

In the world of traditional documentary photography, ‘lyricism’ is a dirty word. But in Afshar’s hands, the lyrical becomes an instrument of choice. Nowhere is this more assertive than in her new work In turn 2023, commissioned for the exhibition. Large-scale photographs depict Iranian women who, like Afshar, live in Australia and have watched the women-led Iranian uprising that began in September 2022 from afar. The portraits are something of an elegy, speaking to their shared grief, but also their shared hope. The women are mostly shot from behind against an overcast sky in tightly cropped scenes. They embrace, tenderly, and braid each other’s hair. Braiding is an intimate and personal gesture, but it is also a revolutionary one. We see the same action in many of the images streaming out of Iran on social media: women with their heads uncovered, braiding and caressing each other’s hair. It is a gesture of defiance through which the women are, quite literally, risking their lives.

Afshar understands the power that metaphor and lyricism can wield, how a staged image can render truths visible, not just representationally but emotionally. This is a radical proposition in itself. The emotion in her work is neither meek nor mute, it is active and assertive. What binds Afshar’s work is its resolute insistence on the humanity of the people she depicts. This is what she contributes to the discipline of the ‘documentary’. Hers is an art that enacts, and makes possible, a poetics of empathy. Afshar doesn’t simply alert us to injustice. She implicates and implores us all.

This is an edited extract from the book ‘Hoda Afshar: A curve is a broken line’, available from the Gallery Shop

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine