A grande dame in the frame

Louise Hersent’s Portrait of a young woman leaning on a meridienne 1828 (right) on display in the Grand Courts. Immediately to its left is one of the paintings that helped inform the frame research

The Art Gallery of New South Wales has acquired a 19th-century painting, Portrait of a young woman leaning on a meridienne, by French artist Louise Marie-Jeanne Hersent with funds provided by Art Gallery members.

The Art Gallery’s senior frames conservator Barbara Dabrowa, frames conservator Genevieve Tobin and reproduction frame maker Tom Langlands lead us through the intricate process of creating a frame fit for Hersent’s painting.

Genevieve Tobin: When the painting came in for a proposed acquisition and I went down to assess it, the frame that was on the work was a commercial moulding that was attempting to recall a 19th-century British classical revival style of framing. Commercial moulding is something that is machine cut, machine gilded and machine finished. So it’s got a very ‘cut and paste’ kind of feel to it, that wasn’t appropriate for the painting, which was dated 1828. The proportions of this frame were far too narrow for a painting of its size (90.8 x 71.8 cm image; 92.3 x 73.9 cm stretcher). It had to have some room to feel stately and be historically accurate. We looked at a lot of corroborating evidence – examples of works by Louise Hersent and her husband, who painted in a very similar style to her. We looked at how these and other works from the period were framed. We were also able to look at two little paintings in French Empire frames from the same period on long-term loan to the Art Gallery – these are now on display in the Grand Courts alongside the Hersent. From there we were able to piece together a picture of what we were looking for.

Barbara Dabrowa: We’re in discussions with the curators from the beginning about the date and history of the artwork. Then we look for a clue in the painting. In this painting, we’ve got a few things. We’ve got palmettes on the wall in the background, we’ve got a nice rosette in the furniture and ornamentation on her shawl. This kind of shawl is characteristic of the Empire period in France. This is important because the women who owned them were upper class, so we knew that the depicted woman should have an elaborate frame for her portrait. Taking into consideration the date and all these other interesting things from the painting, we were looking for a French Empire style frame. Frames of the French Empire period mostly have straight sides, with characteristic ornamentation of palmettes and rosettes at the corners and a running ornament inside. There was a fascination with Napoleon’s archeological discoveries in Egypt and Syria in early-19th-century Europe, so the motifs of palmettes and rosettes were very popular.

Genevieve Tobin: All of the extant examples that we looked at had different iterations of what we were after, not the full package. We had to find a balance between what we could locate and what was the right scale. Crucially, we wanted to have the little rosette ornament in the corner of the frame and the palmettes so it had a really strong correlation with the painting and was reminiscent of romanticism which was a feature of this period.

Tom Langlands: The biggest challenge for this particular work was finding the palmette ornament for the outer corners of the frame. It’s great if we have a work that I can take impressions from because then I can get a crisp impression, firsthand. We had those two little frames as a reference point, but in terms of larger palmettes we had nothing that was the right scale. I put a call out to a couple of institutions and a few private framers. An industry colleague of mine had set up his own business and bought the stock of moulds and equipment of an established Australian frameshop that was closing. Fortunately, he had the right-sized impression of a palmette, but it was not in great shape. I think it was an impression of an impression of an impression. Each time you make an impression you lose the smaller details, so I had to get to work to finesse the ornament, but once I had it and I could measure it properly, I could work on the frame, set the dimensions and the shape. We ended up going with an ogee profile where it kind of curves like an ‘S’.

Barbara Dabrowa: When trying to establish the right size of the frame, we took the face of the woman in the portrait as a reference point. The length of her face, from temple to chin, translates to the width of the frame. We had to make sure the proportions were right, and we recognised this equivalence on portraits from the same period.

Elements of the timber frame are shaped and joined to make the final frame profile.

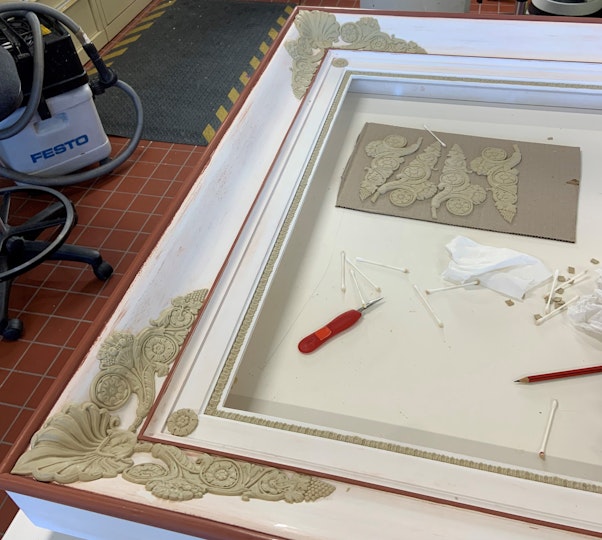

The original ornament casts as supplied.

A positive ornament is pressed in ‘compo’ and then carefully sliced off the base so that only the ornament remains.

Negative and positive impressions of frame ornaments taken for the new frame, and the resulting moulds in white resin

Raw ‘compo’ ornaments are applied with animal glue to the gessoed frame.

The freshly gilded frame with 23 karat gold leaf. It is very bright in this state and must be patinated with a thin film of tinted varnish and subtly ‘dirtied’ to give it an aged look.

Tom Langlands: The impressions of the palmette, two scrolls and grapes came as separate ornaments. Because the impressions are taken from the undulating surfaces of frames, you have to flatten them out to make a usable mould. Initially you’ll get a negative impression from a frame which you have to turn into a positive impression. Once you’ve got a positive impression you can use tools to finetune it. There might be cracks in the original and losses so I carve them back in. I use Zetalabor, a silicone-based dental mould material, to make these impressions. It smells a bit minty because it’s usually used to take impressions of teeth. Then I pour a resin over the top and create a final mould.

Composition or ‘compo’ is pressed into the resin moulds to create the ornaments. To make compo we use a traditional recipe of chalk, tree rosin, animal hide glue, rabbit glue and glycerol. We mix it all together – it’s kind of like making a pizza dough, because the chalk is floury. You end up with these nice flat ornaments, which I freeze to stop them drying out until I’m ready to apply them to the frame. Once the profile of the frame is cut and joined, you steam the ornaments to make them malleable and apply them onto the frame using animal-hide glue, following any curves. For the rosettes, we weren’t able to collect any impressions, so I handmade them based on the meridienne in the painting.

Once the ornaments were attached, I prepared the frame for gilding. I applied an oil size to the surface, then the next day I started the gold leaf. For the burnished areas I applied a bole of red clay mixed with gelatine over the gesso, and once dry I brushed water onto the bole, reactivating the tacky gelatine, and dropped the gold onto it in a process called water gilding.

Barbara Dabrowa: This is traditional water gilding. It has to dry to a certain point and then it can be burnished using a burnisher made of agate. If a freshly gilded surface is too dry it would be ruined, and if it is too wet it would be ruined. So the skill of the gilder is essential.

Tom Langlands: The very final process is to patinate it, that’s to give it a bit of age, to put a bit of dust in the corners and to make it look like it has had a bit of a life, otherwise it’s just too strikingly gold among the older works. I put a little bit of dust here and there and I often use a graphite pencil to draw in some lines and give them a sort of dirty look. Then we fit the painting to the frame.

Genevieve Tobin: There has been an attitude towards frames that they’re disposable, changeable with fashion. However, they are heritage objects in their own right and are reflective of their time.

Barbara Dabrowa: When artists or framemakers designed the frames for new paintings in the past, they reflected the style of everything around – architecture, furniture – and often picked up what’s inside the painting. Now we’re trying to do the same and design frames in the right style.

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine