Menu

Archie 100

A Century of the Archibald Prize

Courting controversy

Courting controversy

From the outset, controversy has courted the Archibald Prize. In 1922, artists John Longstaff and George Lambert were deemed ineligible for the award, on the grounds of residency, with both artists maintaining London studios. Over the decades, works have been censured when the appropriateness of the sitter was questioned. In particular, the use of the term ‘distinguished’ in JF Archibald’s will provided ammunition for detractors, who have also at times begrudged the inclusion of sitters who aren’t ‘Australian’, despite sitters’ nationality or residency not forming part of the entry conditions.

In the 1930s and 1940s, however, a different battle was played out on the walls of the Archibald. A cohort of artists supporting modern trends in art sparred in the press with members of the newly established Australian Academy of Art, with its largely conservative outlook. This led to the biggest controversy in the history of the prize, in which two artists took the Gallery trustees to court after they awarded the 1943 Archibald Prize to William Dobell, for his portrait of artist Joshua Smith.

WB McInnes, winner Archibald Prize 1924

Miss Collins

In 1924, WB McInnes created a stir when he took out the Archibald Prize with this portrait – not because it was one of five works by him in a field of just 40 entries or his fourth consecutive win, but because of his subject.

Gladys Neville Collins (1890–1960) was the daughter of Joseph Thomas Collins, a lawyer and state parliamentary draughtsman and trustee of the Public Library, Museums and National Gallery of Victoria. She had appeared in George Lambert’s The white glove 1921 (not an Archibald work) – a portrait that was admired by art connoisseurs; McInnes acknowledges the painting in this portrait’s composition. However, Archibald commentators were in uproar about whether the Melbourne socialite was ‘distinguished’, an attribute mentioned in the prize’s entry terms. Literary critic Alfred Stephens, writing from Perth, deemed the award conditions had not been met: ‘A portrait of Tom, Dick or Mary Anne is less valuable to Australia than a portrait of a person who has given distinguished service to national life’.

There was a similar reaction to McInnes’ 1923 win for Portrait of a lady, depicting his wife, the artist Violet McInnes (whose own portrait of Sybil Craig is in Archie 100), and again in 1926 when he won with Silk and lace, a portrait of artist Esther Paterson (whose portrait of her sister Betty Paterson is also included in Archie 100).

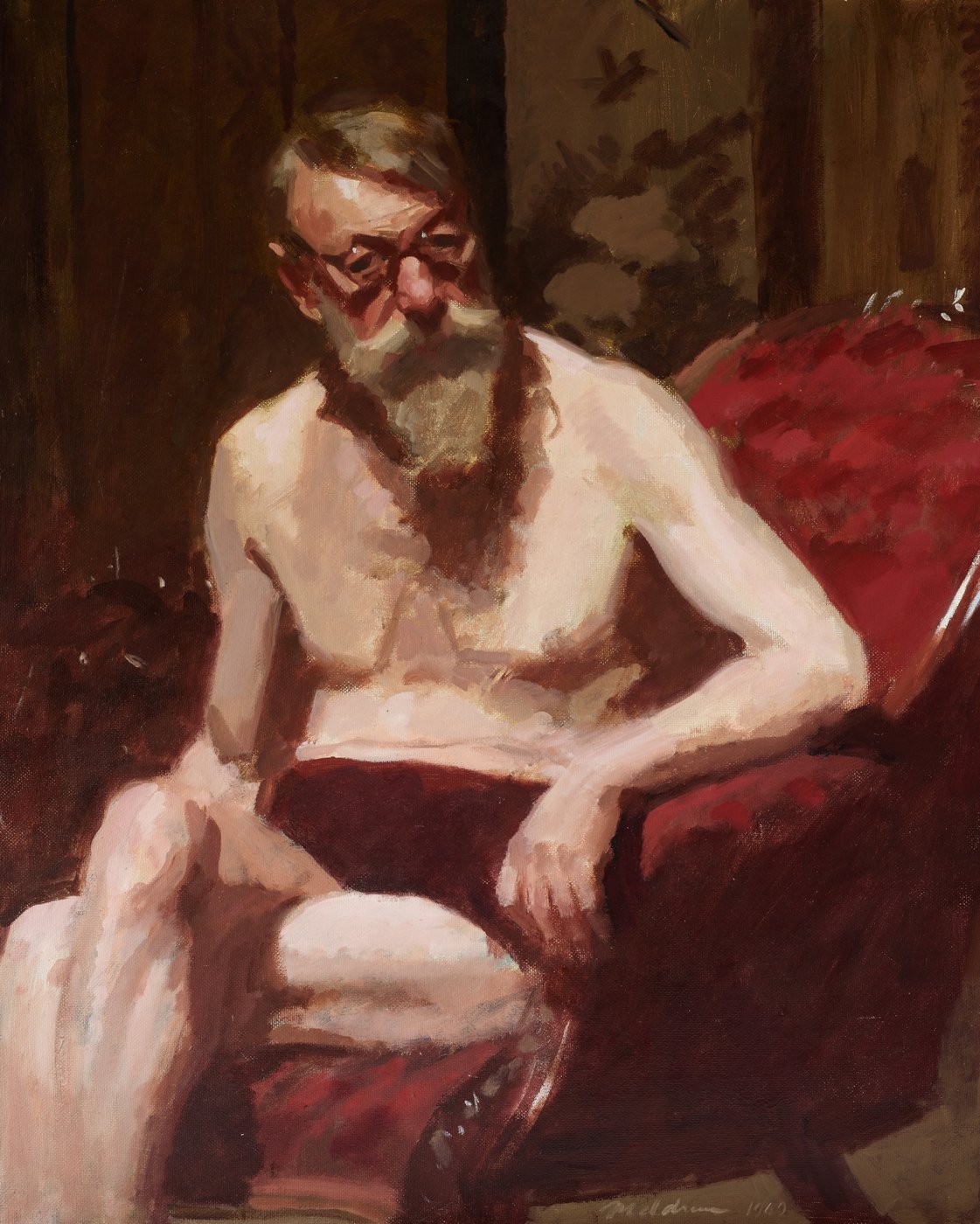

Max Meldrum, Archibald Prize 1949

Self-portrait

A controversial but highly influential figure in art circles, Max Meldrum arrived in Australia from Scotland with his family at 14 years. Following his studies at Melbourne’s National Gallery School, he was awarded the 1899 National Gallery of Victoria Travelling Scholarship and returned to Europe, spending almost 12 years in France. Absorbing works by the likes of Diego Velázquez and rejecting the post-impressionists and cubists, he cemented his dedication to realism, decrying modern art as a ‘pathological symptom of the diseased condition of modern civilisation’. Meldrum returned to Melbourne, established an art school, and wrote a ‘manifesto’ on his theories of tonalism, Max Meldrum: his art and views (1919).

When Nora Heysen – at just 28 – became the first woman to win the Archibald in 1938, Meldrum’s controversial public stance pillorying her success was unyielding. The 63-year-old declared, ‘If I were a woman, I would certainly prefer raising a healthy family to a career in art’. He was contentiously appeased when the trustees awarded him both the 1939 and 1940 Archibald Prize.

Despite his orthodox and polarising views, which fuelled the rancorous conflict between artists of the academic and contemporary camps in the late 1930s, Meldrum’s skill with the brush is unequivocal. This semi-naked portrait of his 75-year-old self attracted frenzied attention, much to Meldrum’s vainglorious delight.

Arnold Shore, Archibald Prize 1935

HV (Doc) Evatt

Arnold Shore was one of a group of artists whose restrained form of modernism muddied the waters in the clash between avant-garde and traditional art in Australia during the 1930s. Shore studied at Melbourne’s National Gallery School and briefly with tonalist Max Meldrum. However, he soon began painting works strongly influenced by post-impressionism, particularly Paul Cézanne. In 1932, Shore opened a school with modernist artist George Bell. It was around that time that Shore met politician and judge Herbert ‘Bert’ Vere Evatt (1894–1965) and his wife Mary Alice Evatt (1898–1973), both spirited supporters of modern art. They provided Shore with his first commission: this Cézannesque portrait of Bert, shown in the 1935 Archibald Prize.

The partnership between Shore and Bell didn’t last. In 1937, while still producing post-impressionist-inspired works, Shore joined the conservative Australian Academy of Art. Vehemently opposing the Academy, Bell established the Contemporary Art Society in 1938, strongly supported by the Evatts.

When William Dobell won the 1943 Archibald with his portrait of artist Joshua Smith – with Mary Evatt, the first woman appointed a trustee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, voting in his favour – the clash between the conservative and contemporary groups erupted. Like Shore, Dobell had exhibited with both groups (although neither artist represented the radicalism present in the two camps). It was only Dobell, however, who got caught in the crossfire.

Grace Crowley, Archibald Prize 1933

Portrait in grey

Grace Crowley was one of a group of Sydney artists whose progressive works challenged the prevailing conservatism of the Archibald Prize in the 1930s. Such modernist portraits were antithetical to the traditional work of WB McInnes, Charles Wheeler and John Longstaff, all respected – and winning – Archibald artists in the 1930s.

Crowley’s decision to become a professional artist was extraordinary for her time. Against her parents’ wishes, she moved from rural New South Wales to Sydney and established a successful career as an artist and educator. Studying with Julian Ashton from 1915, then becoming his assistant and a teacher at his school, she left for France in 1926 with fellow instructor Anne Dangar. In Paris she absorbed the theories of cubism at André Lhote’s academy, then under Albert Gleizes, who influenced her development towards complete abstraction in the 1940s. Returning to Australia, Crowley joined artist Dorrit Black – with whom she had painted in Europe – in Sydney at her newly established Modern Art Centre. In 1932 Crowley established the Crowley–Fizelle School with painter Rah Fizelle. Crowley, Black and Fizelle were all Archibald artists between 1930 and 1933.

Crowley’s 1933 Archibald work shows the artist’s pure assimilation of Gleizes’ teachings, and is one of her most abstracted portraits, with foreground and figure converging through the fragmented and faceted planes of grey green.

Recent research has uncovered the subject of this work: Marjorie Roberts, a professional artist’s model, who also sat for Dorrit Black and Arthur Murch in Sydney to support her family during the Depression.

EA Harvey, Archibald Prize 1932

Portrait of Margaret Coen

Edmund Arthur Harvey’s drawing skill led him to full-time studies at Julian Ashton’s Sydney Art School as a teenager. He left for Europe in 1925 and spent two years studying in Paris and then London.

With celebrated artist George Lambert as his mentor, coupled with a trademark polished rendering of tone and texture, his selection for the newly formed conservative Australian Academy of Art in 1937 was a certainty. One critic, modernist George Bell, believed the Academy’s establishment would sanctify banality and preserve mediocrity. Fear of unfamiliar trends in modern art drove membership, while dread of an official, conservative body determining the ‘standard’ of art prompted other artists to join the Contemporary Art Society, formed in 1938.

Although it was painted five years before Harvey joined the Academy, this stunning portrait of then 23-year-old artist Margaret Coen (1909–93) verifies Harvey’s astonishing facility for drawing, which his admirers felt gave his work a ‘genuine feeling of romanticism’. However, his detractors thought his portraits ‘frigid’. The sharp divide between opposing groups today seems unfounded, prompting the question: why the controversy?

Nevertheless, for Harvey, his Academy membership gained him prestigious commissions. In 1937, he won a competition to produce 12 relief panels for the façade of the Queen Victoria Building, depicting the history of European settlement for Sydney’s sesquicentenary celebrations, to public acclaim.

On display at the Art Gallery of NSW only. Not part of the Archie 100 tour.

William Dobell, Archibald Prize 1943

The billy boy

William Dobell has an almost legendary place in the Archibald pantheon, thanks to his 1943 winning portrait of artist Joshua Smith. That win was challenged by a group of artists, led by Mary Edwell-Burke and Joseph Wolinski, who took Dobell and the Gallery to court, claiming the work was a distorted caricature, not a portrait. The experience was soul-destroying for both Dobell and Smith, despite the court ruling in Dobell’s favour. The painting was all but destroyed in a fire in 1958.

What is often overlooked is that Dobell exhibited two other portraits in that most controversial year in the prize’s history. One of them was The billy boy, painted at Rathmines RAAF Base during World War II, where Dobell worked with Smith as a camoufleur and artist for the Civil Constructional Corps. Dobell paints the site’s tea maker, Glaswegian Joe Westcott – a heavily tattooed former marine – using his distinctive technique, layering veils of oil glazes. Westcott was a local identity at Wangi on Lake Macquarie, north of Sydney, where Dobell escaped to his parents’ holiday cottage following the Archibald controversy. Wangi was the setting for the landscape painting that won Dobell the 1948 Wynne Prize, the same year he won the Archibald with his portrait of artist Margaret Olley, making him the first artist to claim both in the same year.

Mary Edwell-Burke, Archibald Prize 1932

Exhibited as Mary Edwards

Self-portrait

Mary Edwell-Burke is remembered for her notorious role as the principal campaigner against William Dobell’s 1943 Archibald win for his portrait of Joshua Smith, which led to her and another artist, Joseph Wolinski, suing Dobell and the Gallery. Her single-minded desire to win the Archibald, however, was her undoing, and cast a shadow over the rest of her career, resulting in vetoed portrait commissions, and sustained disparagement from her detractors. Yet her involvement in the prize dates to 1921. Edwell-Burke was a regular Archibald exhibitor over four decades – often with self-portraits – including this 1932 work, with its magnificent hand-carved frame. (Wolinski was the all-time record holder, exhibiting 107 works between 1921 and 1951.)

Edwell-Burke was born Mary Burke and was the half-sister of another Archibald artist, miniaturist Bernice Edwell. To avoid censure through her mother Rose Burke’s liaison with the married Henry Edwell, mother and daughter assumed the surname Edwards. Following studies in Brisbane and Sydney, she trained in Paris, where – at just 19 – her work was hung in the Salon. She was a member of many New South Wales art societies, including the Australian Academy of Art. A daring traveller, Edwell-Burke eventually found her home in Fiji, after decades painting the lives of Pacific Islanders.

This self-portrait was painted at Mount Wilson, in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, where Mary and Rose Edwards ran the guesthouse ‘Wildflower Hall’ in the grand mansion Dennarque. Edwell-Burke sits resplendent in her garden, surrounded by Australian fauna and flora.

On display at the Art Gallery of NSW only. Not part of the Archie 100 tour.

Joshua Smith, Archibald Prize 1943

Dame Mary Gilmore

Despite his notable 67 Archibald portraits, painted over seven decades, Joshua Smith is now mostly remembered as the subject of William Dobell’s contentious 1943 winning work. The fact that his own portrait of acclaimed writer Mary Gilmore (1865–1962) was the runner-up that year is largely unknown. Also forgotten is Smith’s 1944 win – for a painting of politician John Solomon Rosevear – which was seen by many as a consolation prize, as Dobell was, by then, a Gallery trustee and Archibald judge.

Dobell and Smith’s friendship was irrevocably damaged by the court case involving the 1943 award that challenged the painting’s legitimacy as a portrait (many felt it was closer to caricature). Art critics, gallery directors, artists, even medical experts were called on for their opinion, and Smith’s appearance was put under intense and humiliating scrutiny. Behind the scenes, Gilmore acted as Smith’s champion. Ultimately, Smith believed the actions of the artists who instigated the court case – Mary Edwell-Burke and Joseph Wolinski – were impelled by their fear of the changes in art driven by modernism.

As an artist, Smith himself was dedicated to capturing the intrinsic personality of his sitters; his consummate skill as a draughtsman was honed through lessons with Adelaide Perry at Julian Ashton’s art school, following several years of study at East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School).