‘Untitled (WWDTCG)’ 2020

Daniel Boyd Untitled (WWDTCG) 2020, collection of Anthony Medich, Sydney © Daniel Boyd, photo: Luis Power, courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

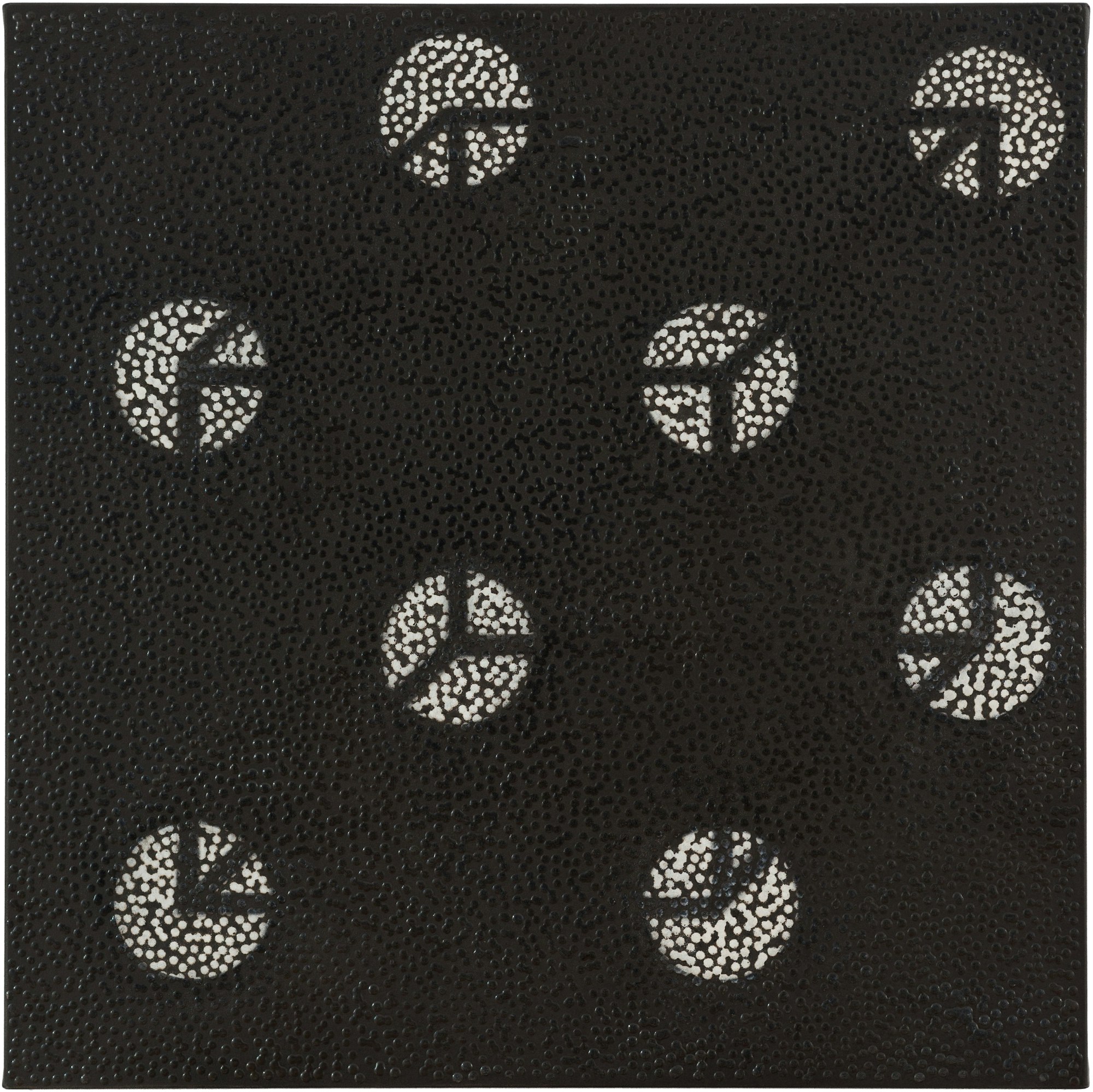

Untitled (WWDTCG) 2020

oil, charcoal, pastel and archival glue on canvas

Collection of Anthony Medich, Sydney

At first glance, this painting is sparse and abstract. Yet if we take a longer look, a form begins to emerge. We imagine the intersecting lines at the centre of the painted circles extending outwards to form a cube. We connect the dots, so to speak. The shape that is evoked here is a Necker cube – an optical illusion in which a two-dimensional image is perceived as a three-dimensional cube with an ambiguous orientation. The cube can alternately be read as facing either the right or the left.

First described by Swiss crystallographer Louis Albert Necker in 1832, the Necker cube has been used to prove the elasticity of human perception and has shed light on the workings of our visual-neural system. In the version of the cube that Boyd has painted, the line-work is merely implied. Our minds must first bridge the omissions to then engage with this play of perception. And in doing so, we re-enact the experience of looking at a Boyd painting. We reconcile fields of invisibility in order to see.

Plain English version

This artwork is made of oil, charcoal, pastel and glue on canvas. It is owned by Anthony Medich, Sydney.

If you look closely, you can see a cube – a Necker cube. It could be 2D or 3D. We don’t know if it is facing right or left.

Necker cubes have been used to show how our brains work when we see. Louis Albert Necker of Switzerland, who studied crystals, first described these cubes in 1832.

In Boyd's cube, the lines are not connected. You have to figure out what they would look like. Daniel Boyd’s paintings make us look for things our eyes can't see.

Untitled (WWDTCG) is a square painting, measuring 87 x 87 centimetres, in oil, charcoal, pastel and archival glue on canvas. It was painted in 2020.

The black canvas has eight regularly spaced white circles each about 12 centimetres in diameter. They are paired and spaced equidistantly on the canvas, alternating from lower left to upper right, as if jumping from side to side in four rows as they move up the canvas. Within each circle three straight black lines, about 2 centimetres in width, radiate from the centre, intersecting with the outer edge of each circle at varying angles.

The circles appear luminous within a dark background, their surfaces covered with slightly raised white dots. Boyd refers to the dots as ‘lenses’, as ways of controlling what we see and as a tool withholding selected information. The three-dimensional textured surface created by the lenses causes the light to bounce off the surface of the painting.

Initially it seems as if the lenses appear only in the white circles; however, the entire surface of the canvas is covered in lenses, each slightly separated from its neighbour.

The work plays with our perception. Our mind jumps and fills in the gaps, so that the black lines within the eight white circles gather to describe the eight corners of a three-dimensional box. The illusion of a geometric cube flickers through the darkness. It’s as if a tight spotlight hits each corner of a transparent cube and only its black-lined corners are visible. There are no clues as to whether the box recedes or juts towards us – it flickers from one possibility to the other.

This is the end of the audio description.

-

01

Audio description