Menu

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection 25 Jun – 23 Oct 2016

Mexicanidad

Diego Rivera, 'Sunflowers', 1943

Mexicanidad is that special quality of being Mexican, one’s Mexican identity … and the pride felt in being Mexican.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera had a shared mexicanidad. It was an identity born of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures and its colonial past, all mixed up with a post-revolutionary, modern, visionary future.

As key members of Mexico’s mid 20th century cultural and intellectual elite, Frida and Diego both contributed to this new understanding of ‘Mexicanness’ that was part of the socio-political movement – and cultural renaissance – that was taking place in the country.

Enlarge

Diego Rivera, 'The healer', 1943

One of the key ways the country was redefining itself was through the rediscovery of its pre-Columbian and indigenous heritage.

Before the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), the country’s mixed indigenous and Spanish colonial background had been a source of both fascination and discrimination.

After the revolution, this hybrid identity became something to be celebrated as distinctly ‘Mexican’.

This was a new notion – ‘mestizo nationalism’ – that took hold in post-revolutionary Mexico, allowing Mexican arts and culture to be reborn in service to a new modern and democratic nation state.

A mestizo is a Mexican of mixed Spanish and indigenous, ancestry – and it’s something Frida, particularly, identified with.

Enlarge

Diego Rivera, 'Modesta', 1937

Mexico’s elite artists were recruited into service for a new centralized, nationalistic cultural program that included the mural painting program that made Diego famous.

He and his fellow muralists – David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco – were known as ‘Los Tres Grandes’, the ‘three great ones’ of Mexican muralism.

Diego helped visualise this new Mexican identity through his revolutionary murals as well as his tender portraits of the Mexican people.

He was especially active in publishing manifestos that called for a truly Mexican school of painting, one energised by the revolution and infused with socialism.

Enlarge

Juan Guzmán, 'Frida Kahlo in hospital holding decorated skull, Mexico', c1950s

Frida too would ensure that every aspect of her life – from her home and garden, to her painting, and even the clothes she wore – conveyed her pride in being a mestizo woman.

In her mexicanidad, Frida helped popularise motifs such as calaveras – the decorative, often edible, skulls made from clay or sugar – and the huge papier-mâché Judas effigies from Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebrations (El Dia de los Muertos).

In fact, both Frida and Diego had been influenced by artists like José Guadalupe Posada, who famously reimagined the skeletons, traditionally part of the Day of the Dead, in his politically satirical posters and pamphlets.

Enlarge

Frida Kahlo, 'Diego on my mind (Self-portrait as Tehuana)', 1943

After her wedding to Diego, Frida took to wearing the Tehuana style of dress from the region of her mother’s part-Indian family.

The ‘Tehuana dress’ is the traditional dress of Zapotec women from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the Oaxaca region.

Tehuantepec was considered – if only to a limited degree – a matriarchal society within a largely patriarchal Mexico. To Frida, the Zapotec women stood as symbols of economic independence and power.

There were three key elements of Tehuana dress: the floral headpiece, the heavily decorated T-shaped blouse or square-cut tunic (huipil), and the long skirt.

Enlarge

Frida Kahlo, 'Self-portrait with red and gold dress', 1941

Frida collected many blouses, huipiles, from different regions throughout the country, including several Mayan-style ones from the Yucatán.

She also used to wear the rabona, an everyday printed skirt, as well as the more elaborate enagua de holán, the embroidered ruffled skirt from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Many contemporary photographs also show Frida wearing a rebozo, the traditional Mexican scarf. She wore the long, rectangular scarf wrapped around her or tied in her hair, and painted herself with it in many of her paintings.

Enlarge

Bernard Silberstein, 'Frida with flowers in her hair', c1940

Diego especially liked the way Frida dressed, saying she wore the clothes of the people.

And Frida chose her clothes for more than political reasons: the long skirts of the Tehuana costume helped elegantly cover up the damaged leg that so troubled her, and the simple blouses concealed the iron corset she was forced to wear in later years.

Frida became famous for these heavily embroidered and beribboned outfits to which she would add elaborate hairdos, floral headpieces, and jewellery: the traditional elaborate drop earrings that we see in countless photos, or modern ones given to her by Picasso.

Enlarge

Juan Guzmán, 'Frida with two birds', c1940s

So powerful an impact did Frida’s look have when she visited the US in 1939, legendary fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli declared she wanted to design an outfit in 'Madame Rivera’s style’.

In fact, Frida had already appeared in a Vogue fashion shoot in 1937 that had made quite an impact in the United States.

In more recent times, leading design houses like Jean Paul Gaultier, Comme des Garçons and Dolce & Gabbana have all designed collections inspired by Frida’s distinctive style.

Frida had developed her mexicanidad into a personal style – more, a persona – and that style was to become iconic.

Enlarge

Hector Garcia, 'Frida Kahlo with Itzcuintli Dog', 1952

Even her pets were symbols of Frida’s patriotic pride. As well as monkeys – considered by the Aztecs to be symbols of fertility – parrots and tame eagles, Frida kept the hairless Xoloitzcuintli dogs native to Mexico.

The dogs, a breed traced back to the Aztecs, were said to act as guides to the afterlife and symbolised Frida’s interest in Mesoamerican mythology. Their name comes from the Aztec god Xólotl and the Nahuatl word for dog, itzcuintli.

Her favourite dog was Señor (or Mr) Xólotl, who made an appearance in several paintings, including one of her most famous, The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me, and Señor Xólotl 1949.

Enlarge

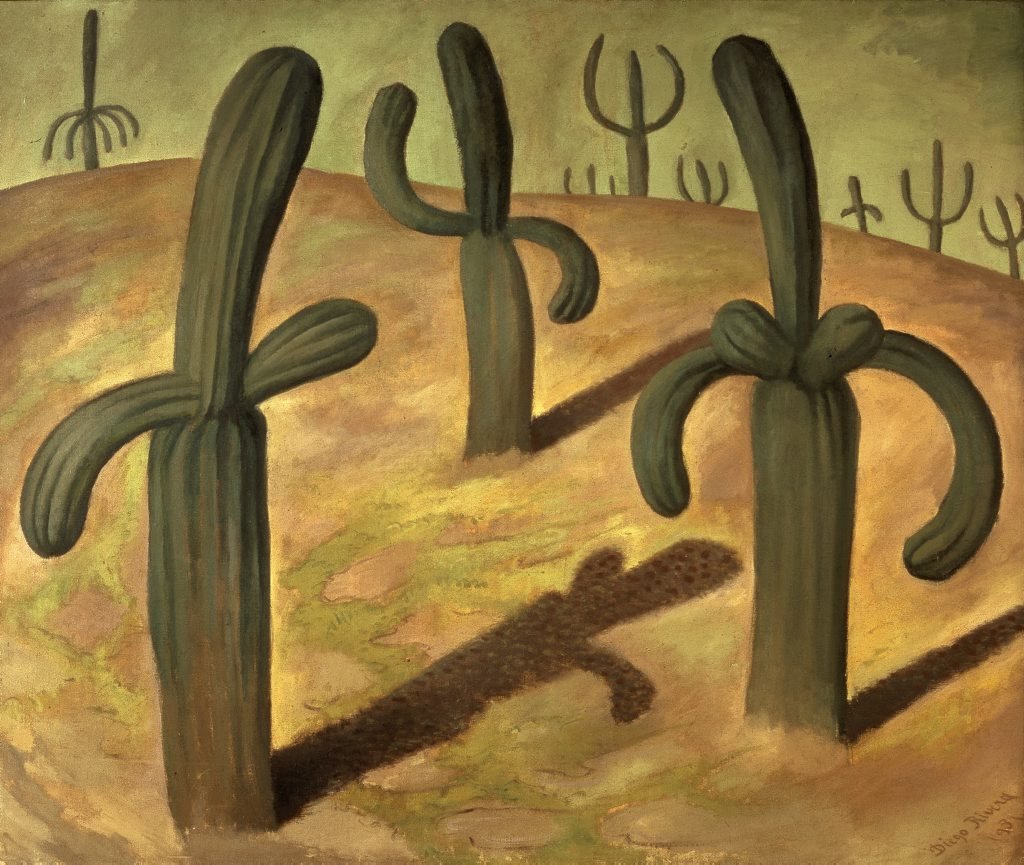

Diego Rivera, 'Landscape with cacti', 1931

Frida brought Mexican motifs into the design of the couple’s home, Casa Azul.

She transformed the garden with indigenous plants such as agaves, aloes, yuccas and cactus. Then she filled it with Mesoamerican artefacts and popular curios – even a small pink pyramid covered in Aztec idols.

Frida also grew native plants for the table – corn, prickly pears and pitahayas (dragon fruits). Some of these would turn up in her late still-lifes, when she made even native fruits emblematic of her pride in Mexico.

‘How we painted the house and the Mexican furniture, all that influenced my painting a lot … I began to make paintings with backgrounds and Mexican things in them.’

Enlarge

Bernard Silberstein, 'Frida with objects on shelves', c1940

Frida loved not only ancient pre-Hispanic art, but also of all sorts of Mexican folk art that she loved to fill the house and garden with: large ceramic pots from Oaxaca, lacquerware from Olinalá, and traditional Talavera tiles.

She also collected retablos. Retablo, or lamina, painting is a folk tradition in Mexico. A type of ‘ex-voto’ Catholic devotional painting, retablos show dramatic scenes of illness, accident or disaster where the person has been saved by divine intervention.

Depressed after her 1932 miscarriage, Diego encouraged Frida to start to paint her life on small sheets of metal in the retablo tradition.

Enlarge

Diego Rivera, 'Calla lily vendor', 1943

Diego once said: ‘The secret of my best work is that it is Mexican’.

Mexican motifs were central to his work – from Aztec mythologies to peasant workers celebrating the maize festival. He painted sweeping murals that depicted the major events in the history of Mexico – and its possible socialist future – as well as small canvases that captured a more intimate portrait of his country.

Diego painted motifs like calla lilies so often they became closely identified with him. In one celebrated work, two women selling lilies in the street have their hair braided in traditional forms that echo the votive positions of pre-Columbian sculptures.

Indeed, Diego’s interest in pre-Columbian art was an obsession.

Enlarge