Real Worlds

Since its inception in 2014, the Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial has served to reveal the extraordinary richness of drawing practice in Australia and its continuing relevance for artists.

Real Worlds: Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial 2020 is the fourth iteration of the exhibition and includes the work of eight artists who seek, through drawing, to interpret and comprehend the world. For some, that reinterpretation is grounded in a deep connection to place or country. For others, it is a reinvention that springs forth from imagination and the subconscious, inflected by subjective experience and rich with narrative suggestion.

In all, the artists have suggested new ways of seeing and making sense of the world, and the relationships between objects, people and places within it.

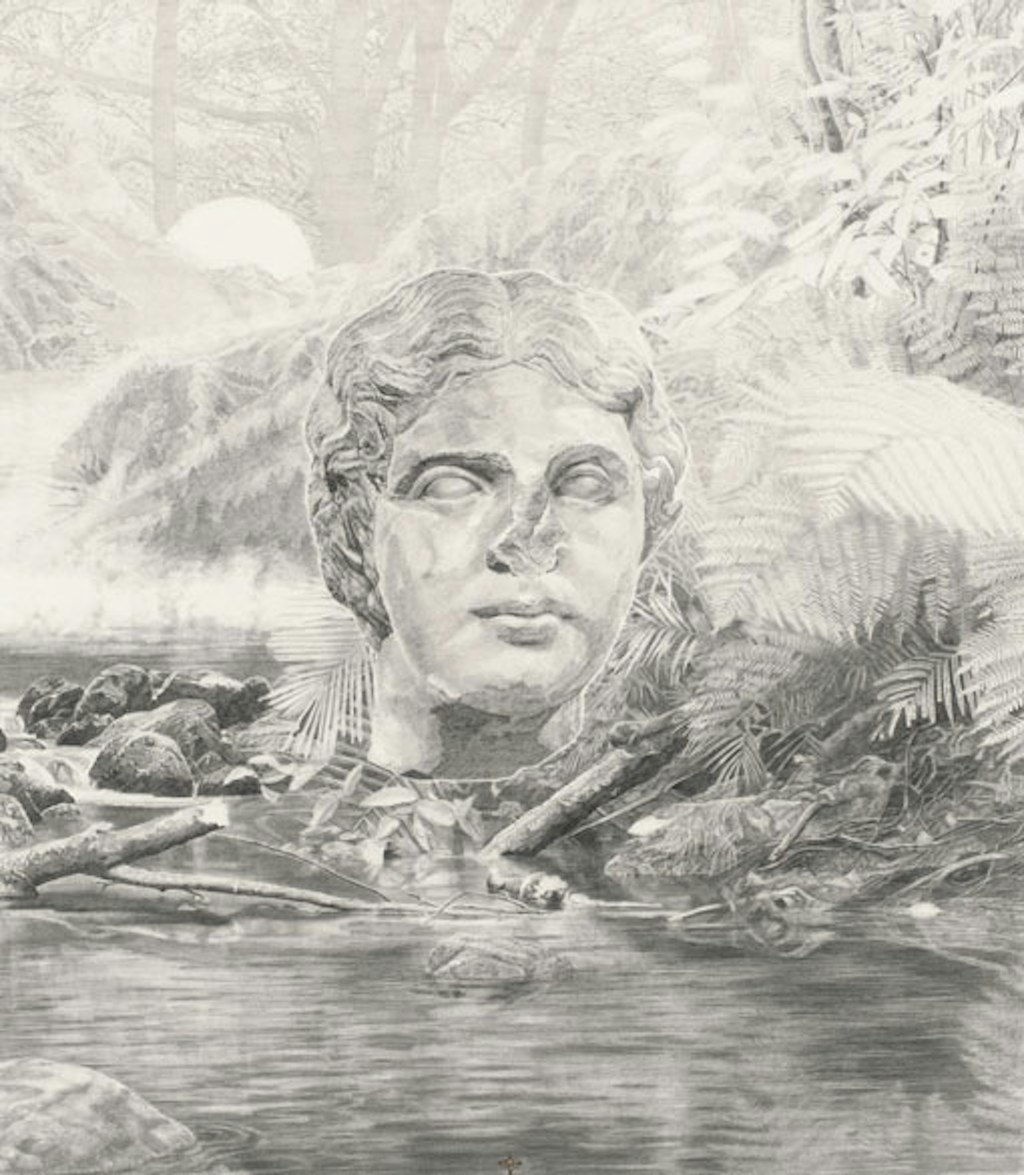

Becc Ország Fantasy of virtue / All things and nothing 2018–20 (detail) © Becc Ország

Becc Ország Fantasy of virtue / All things and nothing 2018–20 (detail) © Becc Ország

Human yearning for utopias lies at the heart of the drawings of Becc Ország. Utilising found landscapes sourced from the internet that she reworks in intricate graphite drawings, Ország echoes the aesthetic of 19th-century engravings and the Romantic sublime. Yet her landscapes are deliberately anonymous, manipulated into mirror-image Rorschachs or studded with gold leaf and drawn symbols, to make them at once familiar yet strange.

Antique heads in chipped marble hover — disembodied, obscure monuments to discarded gods, damaged exemplars of divine perfection from civilisations whose antiquity is dwarfed by the enduring landscapes of fern, water and earth. Within a vast expanse of time, the capacity for humans to find spaces for the sacred remains an enduring impulse.

Jack Stahel’s intricate, complex drawings utilise languages of scientific illustration and taxonomic systems of classification, implying that they’re objective assertions of information. In fact, they are an ‘informative bunch of nonsense’, part of an ‘imaginary science’ that is entirely fictional.

What we first perceive as systems of knowledge of the world in microcosm are, in fact, a reflection of how the human brain seeks to comprehend the world, and ultimately itself. Stahel uses found objects such as exhibition cabinets and plinths to display the drawings, recalling the institutional contexts in which these systems of knowledge can be housed and displayed and the subsequent authority with which they are endowed, through the imprimatur of the museum.

Helen Wright’s pencil drawings of labyrinthine architectural structures emphasise the fragile balance between humanity and the natural world. Her teetering piles of built and industrial detritus project a sense of precariousness, as if the removal of one element threatens the indiscriminate destruction of the collective whole. The structures in the drawings recall the Biblical Tower of Babel in which an ambitious society sought to construct an unparalleled architectural wonder, ultimately doomed to fail as the protagonists could not communicate. A parable to explain the thousands of human languages spoken in the world, the story also illustrates the impossibility of successfully constructing something in the absence of collective understanding. Wright’s drawings are monuments to human folly that stand as cautionary tales against egocentric hubris and the defiance of nature.

Helen Wright Scrap stack freefall in ‘The Age of Stupid’ 2019–20 © Helen Wright. Photo: Peter Whyte

Martin Bell’s ambitious multi-sheet ink drawings are rich with nostalgic associations of a 1980s childhood and grow from his interest in imaginative play and its capacity to create connections between people and things. Incorporating images of found objects including toys and other ephemera, Martin Son of the Universe, What me worry 2018–19 consists of a tangled world of infinite narrative possibility on 75 sheets of paper.

Densely populated with characters including battling robot action heroes of the sci-fi cartoon Transformers and the mascot of Mad magazine, Alfred E Neuman, the characters populate each sheet within rhythmic and pulsating patterns, and on a larger scale in the overall expanse of the drawing. Standing back, one can observe a meta narrative in which two mighty figures engage in combat as fence pickets explode in a crescendo of energy, channelling the geometric balance and compositional structure of a battle painting by Paolo Uccello.

Martin Bell Martin Son of the Universe, what me worry 2018–19 (detail) © Martin Bell

Peter Mungkuri is a senior Yankunytjatjara man from Indulkana in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) lands in South Australia. Born near Mimili, his work is firmly grounded in his knowledge of country, passed on to him by senior men as well as his memories of living and working as a stockman. His lyrical ink and wash drawings depict the different species of trees found there, emphasising the symbolic importance of trees for Anangu culture: ‘the punu (tree) is where our culture starts’, the artist has said.

His role as a senior Anangu man is both to care for country and teach his knowledge of it to younger generations. In fulfilling this through his art and through advocacy for the environment, he protects the culture of his people and keeps it strong. ‘My painting is where it all started. This country is my home. I know this land all over, this is strong country. These things, everything, is my memory – my knowledge. I like painting my country, I like to paint the memories of my country.’

![Peter Mungkuri [w[Punu Ngura (Country with trees) 3]] 2019 (detail), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Aboriginal Collection Benefactors Group 2019 © Peter Mungkuri](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1631771499-170-2019-detail01-m.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

Peter Mungkuri Punu Ngura (Country with trees) 3 2019 (detail), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Aboriginal Collection Benefactors Group 2019 © Peter Mungkuri

Danie Mellor’s ongoing connection with the country of his mother’s family in Far-North Queensland’s Atherton Tablelands leads him to consider the legacy of colonialism and the histories of Australia. His large drawing installations, including the two in Real worlds, feature landscapes rendered monochromatically in blue wax crayon, with intrusions of suspended or collaged figures and objects. These added elements – like the tiny Indigenous figures climbing and collaborating on the boughs of palm trees – are diminutive but assertive additions to what at first glance seems a timeless rainforest glade. We are aware of their presence, curious about their endeavours, but most of all challenged to think on the enduring histories of human occupation of the land.

Danie Mellor A time of the world’s making 2019 (detail) © Danie Mellor

Matt Coyle’s darkly gothic drawings have a dreamlike quality that hovers between real and surreal, sharing an aesthetic with horror films, graphic novels, theatre and literature. Coyle’s process has several stages. First, he constructs ambiguous tableaux of found objects (such as a yellow doll’s house or rubber gloves) in his studio, lights and photographs them, and then draws the images in ink, coloured pencil and acrylic with further manipulations and additions, such as the drawing of his own figure. While independent of each other, the works are displayed in concert – like stills from a movie, single moments wrested from a longer narrative sequence. Their ambiguity and isolation from context elicits an almost primal response that taps into our own fears and inner worlds, as we seek to discover their meaning.

Matt Coyle Night pass 2020 © Matt Coyle

Nathan Hawkes’ lyrical pastel drawings are rich in jewelled colour and seductive textural detail, sharing the dreamy beauty of Odilon Redon’s symbolist work, albeit much larger in scale and with contemporary resonance. Hawkes’ drawings are concerned with form, atmosphere and process while being firmly embedded in everyday life. Wisps of figuration emerge from whorls of pigment, with tangible objects, foliage and suggestions of text revealed and obscured by abstract pulses of atmospheric colour. Produced in a corner of his living room, his drawings are subject to the broader atmosphere of their making – in this case an era of environmental emergency and geopolitical crisis, as well as the everyday dynamics of a family home. His drawings are a poetic evocation of feeling in visual form that comforts as much as it exorcises.

Nathan Hawkes They hear the wind tell of the burned off fields but they are no children no one carries them anymore 2020 © Nathan Hawkes

Nathan Hawkes They hear the wind tell of the burned off fields but they are no children no one carries them anymore 2020 © Nathan Hawkes

The immediacy and intimacy of drawing has a special intensity that is attuned to the times in which we live. In a moment when words seem inadequate and our recent enforced stillness has made us reckon with our feelings in new ways, our human capacity to imagine and reinvent remains a tool for endurance and adaptability. In the absence of individual power to transform monolithic and structural forces that threaten to overwhelm, we have the capacity to imagine something better, or different. The real world can be reckoned with, be re-seen, be understood anew as we face its mercurial challenges. While conceived before our wild year of 2020, and created both before and during it, the Dobell Biennial drawings of Real Worlds speak with urgency and directness to where we are now.

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine

Inside the Real Worlds exhibition

Installation view Becc Ország Fantasy of virtue / All things and nothing 2018–20 © Becc Ország

Installation view (left to right) Helen Wright Scrap stack, the slump 2019–20 and Scrap stack freefall in ‘The Age of Stupid’ 2019–20 © Helen Wright

Installation view Martin Bell Martin Son of the Universe, what me worry 2018–19 © Martin Bell

Installation view Peter Mungkuri Punu Ngura (Country with trees) 1-4 2019 © Peter Mungkuri

Installation view Danie Mellor A time of the world’s making 2019 © Danie Mellor

Installation view Matt Coyle. Various works © Matt Coyle

Installation view Nathan Hawkes. Various works © Nathan Hawkes