The desktop photographs

A workshop participant with Martin Jürgen, viewing greenwork TL #7 and greenwork TL #6, two type C photographs mounted on Perspex, in the exhibition Rosemary Laing: transportation

These days it’s easy to take the fragility of the printed photograph for granted.

We take pictures to capture moments, to freeze memories, to communicate with others, and to tell a story. More and more these stories, presented from our own unique point of view, are being created with digital cameras, low-resolution phones and even web cameras, then shared via social media or online media outlets, stored on computers or on the cloud, and printed using desktop printers, as a record of the event that took place.

While this is no longer unusual, it does present a change to the process of image-making and a challenge to the field of photographic conservation. The notion of the coveted print is being replaced with the understanding of an infinitely reproducible image. In reality, digital prints can be unique objects which constitute a major part of our social and cultural heritage. As many digital prints make their way into institutional collections, those charged with their care need to maintain a high level of knowledge and expertise to ensure the long-term preservation of these works.

To address this need, a symposium and workshop on the preservation of digital prints and contemporary colour photographs was presented at the Art Gallery of NSW by Martin Jürgens, in association with the Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material and the Association of Australian Decorative and Fine Arts Society. Martin is conservator of photographs at the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands and the author of the book The digital print.

Digital printing is just the latest in a long line of photographic and printing processes which have been created to meet consumers’ desire for affordable, easily producible images. In fact, creating reasonably priced, quality digital prints that have the look and feel of a traditional photographic print is the end goal of many of today’s manufacturers of digital printing technology. Digital printing paper is now available in a variety of finishes, including non-reflective matte papers and resin-coated papers in high gloss, gloss or semi-gloss, which more closely resemble traditional prints.

As the technology of digital printing continues to advance, it makes the correct identification of a digital print more difficult for the conservator charged with its care.

As conservators we are taught: First, do no harm. For conservators of photographs, this approach can be adapted to: First, look. Then look closer. Then look again. When photographs conservators look at digital prints we are like detectives who compile evidence and search the scene for clues, hoping we can identify the printing process. Because, in order to recommend the correct course of treatment of a digital print, including display and storage, we first need to know what kind of digital print it is.

While there are things you can see with the naked eye, such as the way the ink sits on the surface of the paper, how light scatters across the surface and how uniform the colours are along the edge of the image, most of the time conservators need to use stereo-microscopy to identify a printing process. Stereo-microscopes magnify a digital print so we can see the individual dot patterns that make up an image. Often these dots form specific regular and irregular patterns that, when compared to a known sample print, can help to positively identify a process. The knowledge to correctly identify digital processes such as Fuji Pictrography, Kodak Pegasus, dye sublimation, electrography and inkjet printing can be gained by acquiring an understanding of ink chemistry and formation of media and the particular surface characteristics of a media support.

Much like works on paper, digital prints are subject to both physical damage and external environmental factors, while also being susceptible to deterioration due to the inherent material composition. As there are many materials and brands, which all interact differently, knowledge of the materials and techniques used in the production of a digital print provides valuable information about the deterioration characteristics and susceptibility to light and moisture, as well as overall chemical permanence. It is understood, however, that digital-era consumers are selecting and buying multiple combinations of inks and papers in order to make prints, and so it may very well be impossible for conservators to accurately determine each individual component of a single image.

Getting into the laboratory and experimenting on test samples allows conservators to push the boundaries of the materials in an analytical and systematic way so we build a better understanding of the limitations of a conservation treatment, as well as more confidence in handling the printed object.

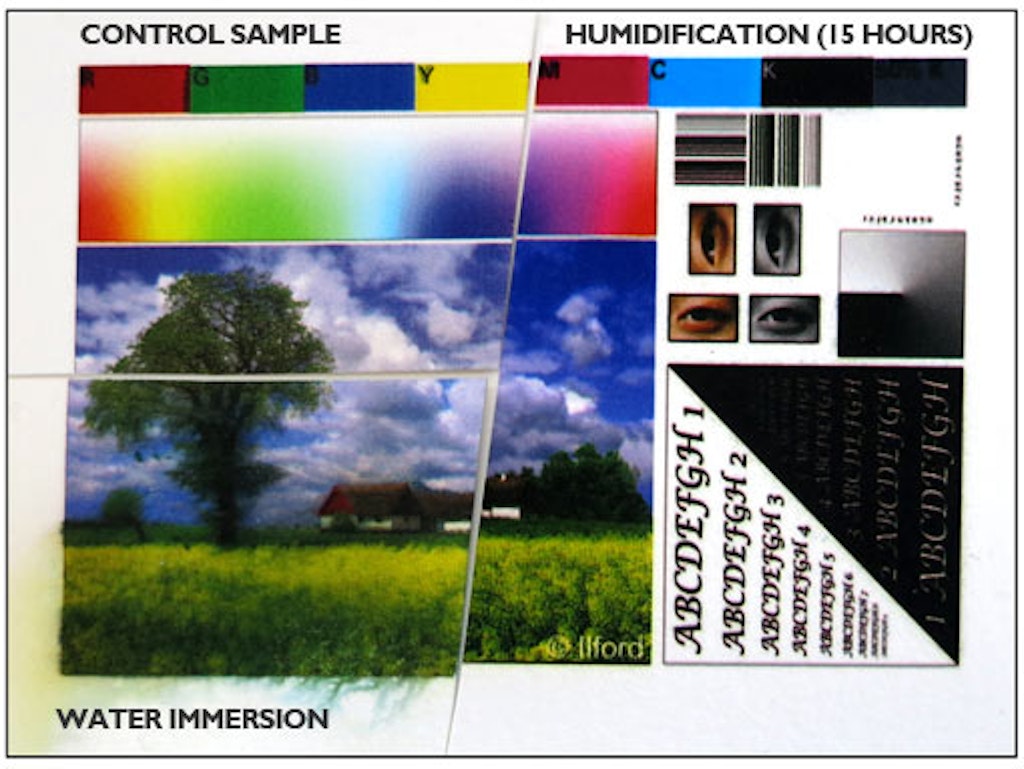

One possible treatment for paper-based objects such as prints and drawings is the washing and humidification of the objects in water baths. This treatment can be undertaken to flatten creased or curled objects and to restore vibrancy to works that are yellowing or discoloured. Due to solubility issues, any object considered for aqueous treatment will first undergo rigorous testing. But at the recent workshop, in the name of science (and because we wanted to see something cool), we placed a sample digital Iris print, which is known to be especially water sensitive, in both a water bath and a humidification chamber in order to test the stability of the ink.

You can see the results in the image below. Full water immersion caused the ink to run profusely; the ink actually started to drift off the paper as soon as it was placed in the bath. However, the passive water-based treatment of humidification caused only a very minimal shift in colour. These results confirmed that any use of solvents or liquids would be very risky and one that we would not undertake on an artwork or cultural heritage object.

As soon as the nature of digital prints is understood, it becomes clear that there is no fixed material, no standardised language and no single strategy for dealing with these works. The difficulty of establishing recommendations and standards in such a rapidly developing field presents multiple challenges to the management of photographic collections. As conservators, we must accept the inherent nature of the medium and that, much like the photographic processes of the past, digital printing will continue to develop and change over time.