Menu

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection 25 Jun – 23 Oct 2016

Lines of connection

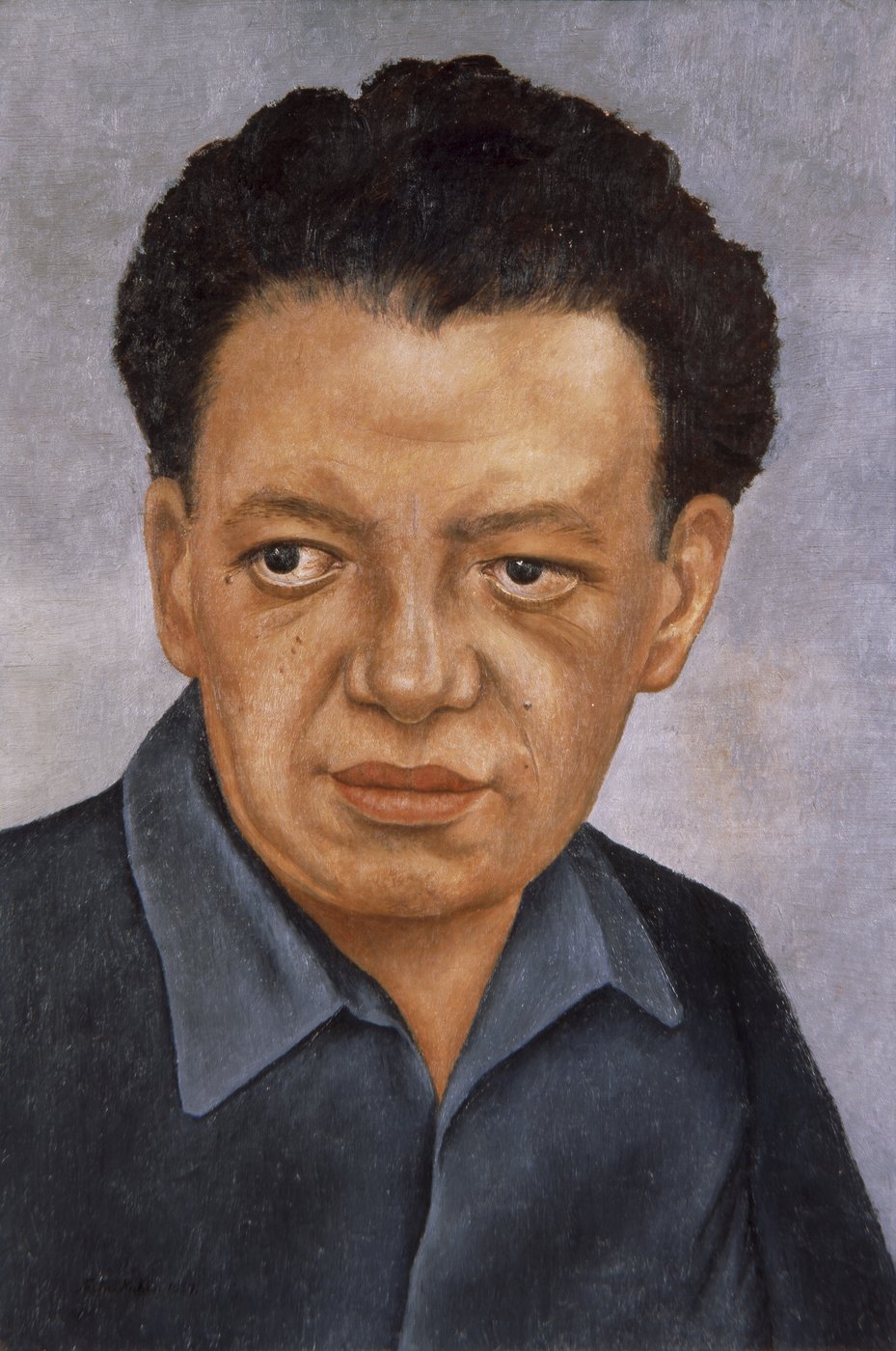

Frida Kahlo, 'Portrait of Diego Rivera', 1937

A precocious talent, Diego Rivera began drawing at three, then studied at night at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City from the age of eleven.

Diego then won a scholarship to study full-time at San Carlos under teachers like Félix Parra, Santiago Rebull, and José María Velasco.

This was the dominant model for art training when Diego was starting out: rigorous formal training at large academies. In Mexico, artists looked to Europe, mainly France and Spain, for techniques, approach and subject matter.

But times were changing and revolution was in the air in Mexico – not just social and political, but artistic.

Enlarge

Diego Rivera, 'The healer', 1943

At San Carlos, Diego would meet the popular satirist and printmaker José Guadalupe Posada and other artists who would have a strong influence on him.

At one stage Diego lead a student protest and was briefly expelled, before joining the first of many groups, the Groupo Bohemio, led by the influential artist Dr Atl, who had brought many new European artistic trends back to Mexico.

After graduating in 1905, Diego got his own chance to go to Europe, gaining an important government scholarship that allowed him to further his studies – and to mix with many of the central characters of modern art.

Enlarge

Diego Rivera, 'Sunflowers', 1943

Diego would spend the years from 1909 to 1921 in Europe; first Spain to study the masters Goya, Velázquez and El Greco; then the Flemish masters in Belgium, where he would meet his first wife, the Russian émigré artist Angelina Beloff.

The pair settled in what was then the most exciting artistic city in the world, Paris.

Diego and Angelina shared a house in Montparnasse with the Dutch artists Conrad Kickert and Piet Mondrian. In the melting pot that was modern Paris, he would become good friends with the Italian Amadeo Modigliani and the Japanese Tsugouharu Foujita.

Enlarge

Diego Rivera, 'Calla lily vendor', 1943

Diego worked hard. When not painting, he was talking about painting, trying to develop his own style.

He started showing at the all-important salons: in 1910 he was at the Salon des Indépendants alongside Matisse, Le Fauconnier, Léger and Metzinger.

While exploring these new modernist approaches and connecting up with visiting Mexican artist friends, cubism was becoming the leading force of the avant-garde.

By 1912, when Apollinaire calls the cubists, ‘the most serious and most interesting artists of our time’, the ambitious Diego couldn’t have failed to notice. By the end of 1913, all his own works were in the cubist style.

Enlarge

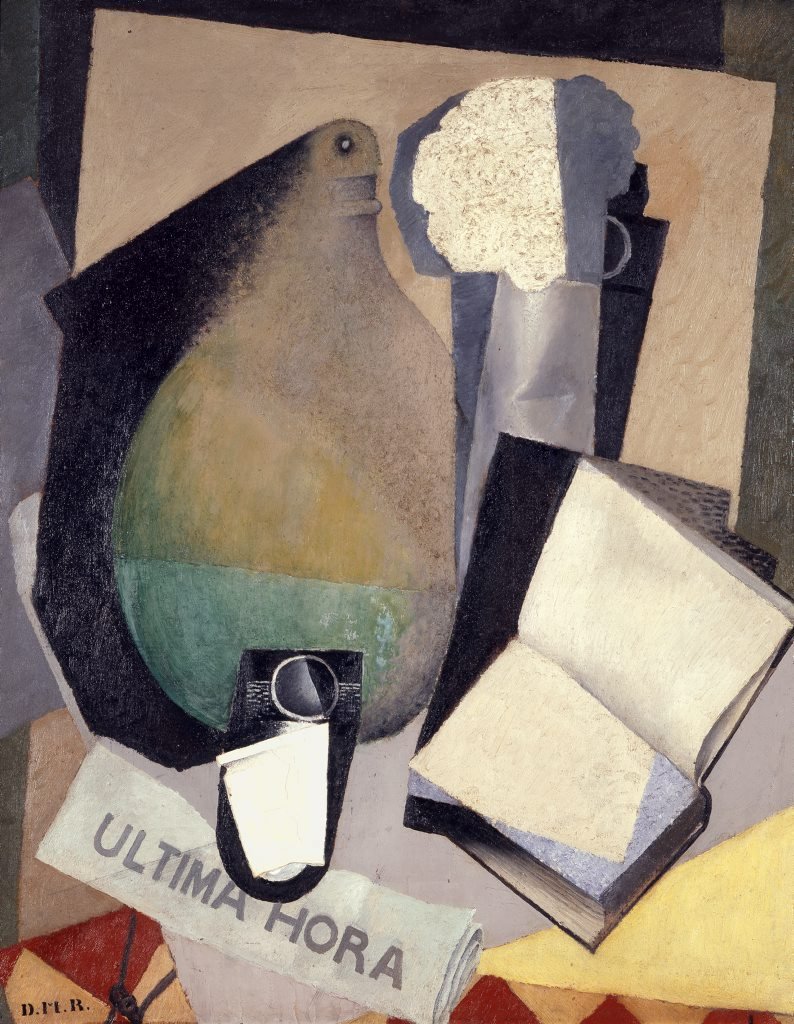

Diego Rivera, 'Last hour', 1915

One day in 1914, Diego was summoned by the acknowledged leader of the avant-garde, Pablo Picasso. Diego walked to Picasso’s studio nervously feeling like ‘a good Christian who expects to meet Our Lord’.

The two Spanish-speakers became good friends. Picasso brought important visitors like Georges Seurat and Juan Gris to Diego’s studio, and his status soared. Before long, in April, Diego held his first solo exhibition in Paris.

But later that year, while holidaying in Majorca, news came that war had broken out.

Before the end of the war, Diego had fallen out with Picasso. It seems the break was part a philosophical dispute over cubism and part some now forgotten sexual rivalry between the two machismo artists.

Enlarge

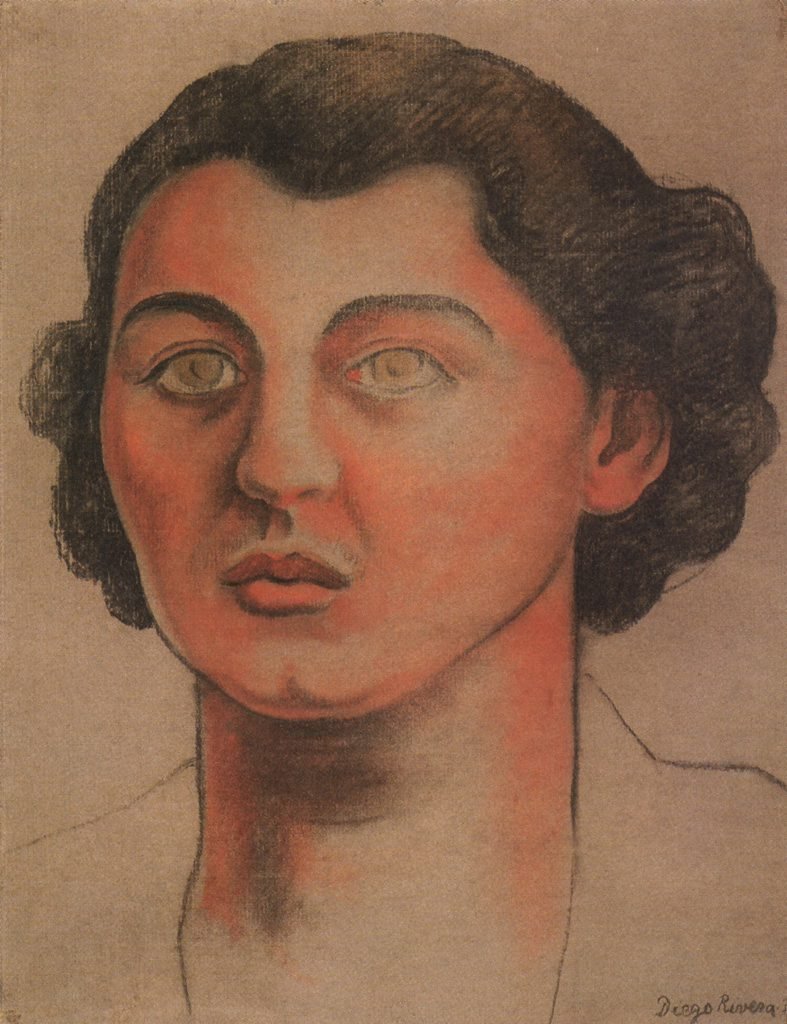

Diego Rivera, 'Portrait of Cristina Kahlo', 1934

In the years abroad, Diego had worked his way through a host of artistic styles from post-Impressionism to cubism. After the break with Picasso, he looked to the art of Henri Rousseau and Paul Cézanne.

Diego was determined to create a socially-engaged art for a modern Mexico, and he finally found it in a mixed modernist ‘realism’.

Diego had rejected cubism – and Angelina – though he was to take up with the first female cubist, Marevna Vorobyev-Stebelska.

Enlarge

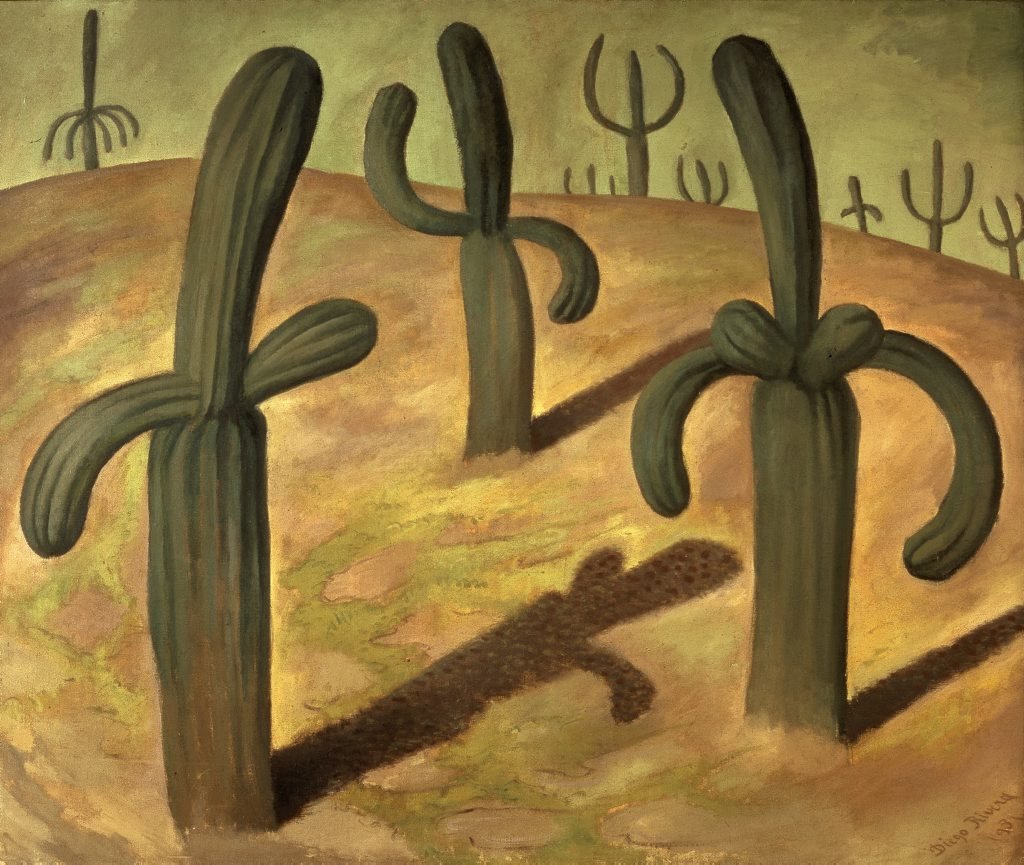

Diego Rivera, 'Landscape with cacti', 1931

Again supported by a grant, Diego travelled to Italy to study Renaissance fresco techniques.

By July 1921, having missed the revolution, he was called back home, enlisted into service as a painter for the new Mexico.

Recruited by cultural ideologue José Vasconcelos, Diego would go on to play a key role in the development of a new post-revolutionary culture for Mexico.

Enlarge

Frida Kahlo, 'Self-portrait with necklace', 1933

It is often thought that Frida Kahlo was untrained before her accident, and that she suddenly, almost miraculously, became interested in painting during her recovery in hospital.

Frida herself liked to encourage this view of her as a self-taught and naïve artist.

In fact, Frida learnt a good deal of her craft from her father Guillermo Kahlo, a respected photographer who specialized in architectural photographs.

Enlarge

Bernard Silberstein, 'Frida paints self-portrait while Diego observes', 1940

Helping her father in his studio, the young Frida learnt to retouch photos – work requiring meticulous care and the use of very fine brushes. She kept this technique of tiny brushstrokes throughout her career, and friends noted she was scrupulous about the care of her tools.

In 1925, Frida was apprenticed to a friend of her father’s, the commercial printmaker Fernando Fernández. He taught her drawing and trained her by having her copy prints. Her favourite, before her accident, was the Swedish printmaker Anders Zorn.

Enlarge

Photographer unknown, 'Diego observing Frida paint 'Self-portrait on the borderline', Detroit', 1932

Though she didn’t know it at the time, when Frida started at the National Preparatory School, she continued with the training that would later help her as an artist.

As part of her preparation to study medicine at university, she took two required courses of study, drawing and clay modelling.

While she was there, acting up with her political Los Cachuchas gang, she also famously watched Diego at work on is Creation mural, teasing and flirting with him as he worked.

She was broadly creative herself at this stage: she was known to have made small drawings and her poem Recuerdo (Memory) was published in the experimental weekly magazine, El Universal Ilustrado.

Enlarge

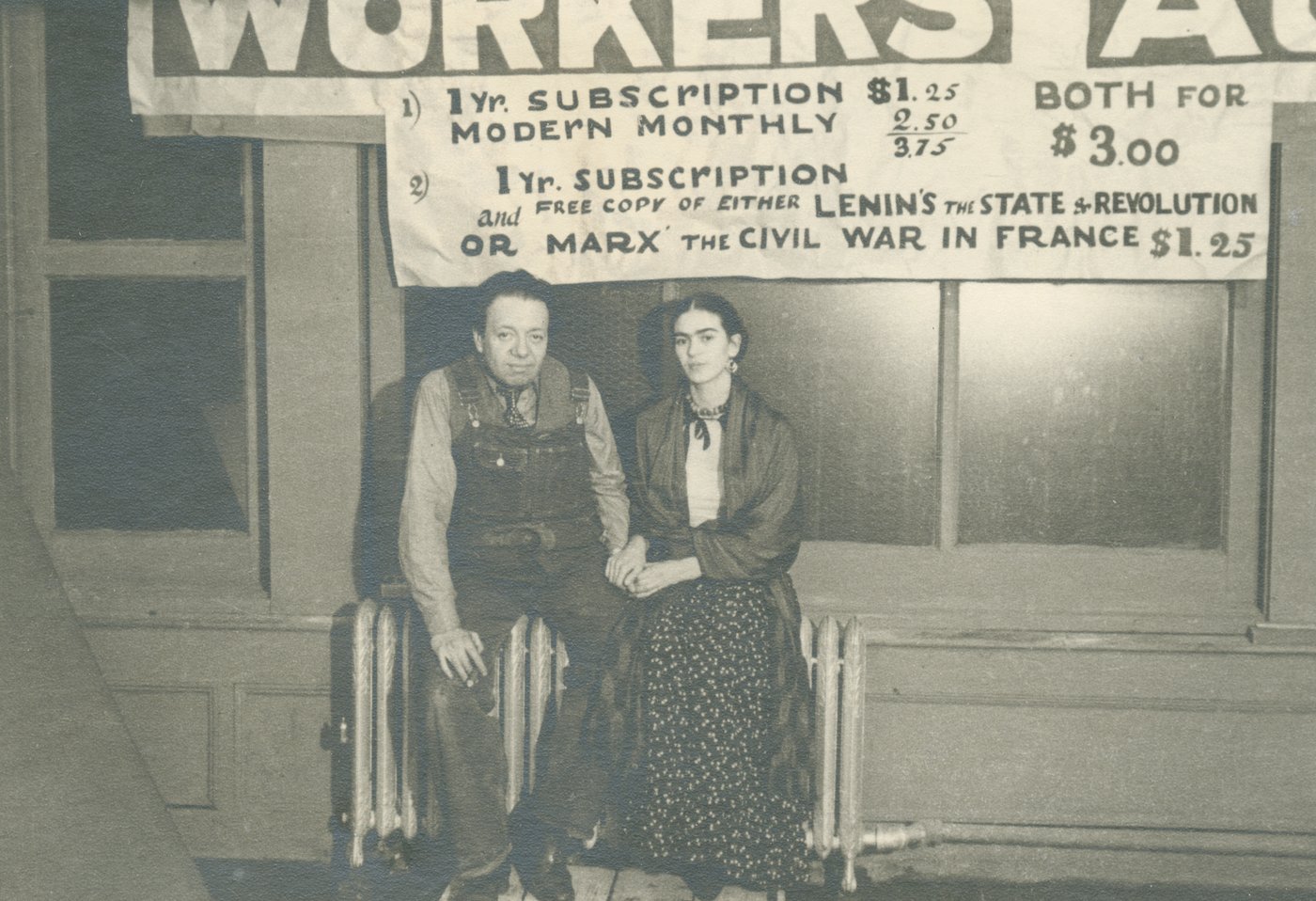

Lucienne Bloch, 'New Workers School, NYC', 1933

The Mexican revolution was a call to nationalism, and widespread radical changes brought about new institutions, new art, and new access to learning. A genuine cultural renaissance was taking place and Frida and Diego were key players.

Open Air Painting schools were opened in the regions, redefining artistic instruction in Mexico, and alternative teaching methods were developed such as the Best Maugard Drawing Method that would influence Frida’s early work.

Before long, people like Diego would be involved in setting up socialist collectives such as the Union of Technical Workers, Painters and Sculptors, later the League of Revolutionary Artists and Writers (LEAR).

Enlarge

Juan Guzmán, 'Frida and Diego by mural 'The nightmare of war, dream of peace' in the Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico', 1952

But Diego was called home to launch into the greatest nationalistic project of them all: the Mexican mural program.

In a glorious moment of post-revolutionary fervour, highly visible government-sponsored murals were being painted in churches, schools, libraries, and public buildings across the country.

Diego, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco would come to be known as ‘Los tres grandes’, the three greats, of epic Mexican muralism.

Enlarge