-

Details

- Date

- 1829

- Media category

- Materials used

- mezzotint with etching

- Dimensions

- 53.4 x 80.0 cm (trimmed to image)

- Signature & date

Signed and dated l.r., [incised] 'J. Martin. 1829'.

- Credit

- Purchased 1960

- Location

- Not on display

- Accession number

- DB4.1960

- Copyright

- Artist information

-

John Martin

Works in the collection

- Share

-

-

About

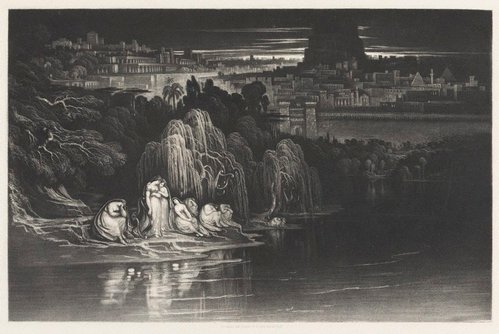

This mezzotint, the most spectacular in terms of size and subject matter ever attempted by Martin, depicts the accomplishment of the scriptural prophecy foretold in the Book of Nahum: that God will wreak vengeance on the wicked city of Nineveh through natural disasters and erase it from the face of the earth. Nineveh was the capital of the ancient Assyrian Empire (modern-day Iraq) and was fabled for its magnificence, but it was also referred to in the Bible as a ‘bloody city … all full of lies and robbery’.

Destruction befell Nineveh when violent floods caused the river to rise and eventually tear down the city’s walls, allowing the Medes and Babylonians to infiltrate the capital. The invading armies are shown in the background of the print as they approach via the river and enter the city through the collapsed fortifications. Under a convulsive sky the doomed Ninevites scatter like ants while their decadent king, Sardanapalus, orders the construction of the immense funeral pyre on which he will burn to death with his concubines and treasures.

Martin was the 19th-century’s master of visual melodrama. By the early 1820s he had attained popular acclaim as a painter of cataclysmic subject matter on an epic scale inspired by antiquity and the Bible. Many of his compositions were reworked into mezzotints, which he produced and published himself. These were avidly collected and provided him with a substantial income, far greater than that realised from the sale of his paintings.

Martin was also a canny marketer of his prints, which he dedicated to the various noble and crowned heads of Europe. When The fall of Nineveh was published on 1 July 1830, it bore the printed dedication: ‘TO HIS MOST CHRISTIAN MAJESTY CHARLES X, KING OF FRANCE & NAVARRE … AS A HUMBLE TRIBUTE OF THE ARTIST’S GRATEFUL FEELING FOR THE HIGH HONOR HIS MOST CHRISTIAN MAJESTY HAS BEEN GRACIOUSLY PLEASED TO CONFER UPON HIM …’ Ironically, within a few weeks of the print’s release, the dedicatee was dethroned during the July Revolution and went into exile.

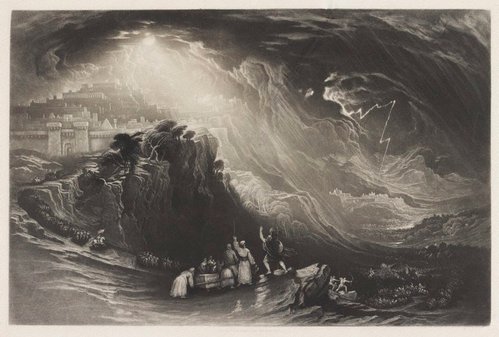

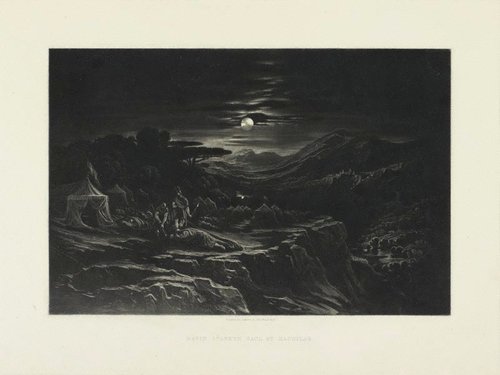

Martin’s early success as a mezzotinter led to his contract with the publisher Septimus Prowett to complete 24 illustrations for John Milton’s epic Paradise lost. The series was issued in two formats, one slightly smaller than the other, and Martin worked on both simultaneously. Unlike earlier illustrations of the poem, which gave prominence to the representation of the figures, Martin’s illustrations emphasise the vast spaces and cosmic settings of Milton’s drama. A new project followed in 1831 when Martin embarked upon his next great series, the Illustrations of the Bible. Examples of both the Milton and Bible sets are held in the Gallery’s collection.

Martin’s grandiose and electrifying imagery expresses for the most part a world composed of forces indifferent to humanity. His conception of the apocalyptic sublime was shaped by the tradition of 19th-century evangelical millenarianism, which stressed imminent punishment and destruction associated with Christ’s second coming. Although we know little of Martin’s actual religious beliefs – his son Leopold suggested that in matters of faith his father was a mainstream Anglican – he nevertheless appears to have had some personal sympathy with the ideas expressed by millenarian sects.

‘Mad Martin’ is a name that perhaps not inappropriately has stuck to the artist, although this sobriquet more correctly applies to his arsonist brother Jonathan who escaped from a lunatic asylum and set fire to York Minster in 1829. Nevertheless, Martin’s art was wildly parodied for its eccentricity and sensational effect, while at the same time being widely appreciated and emulated. Copies and pirated editions of his prints were published in France, where the adjective martinien was already in current usage in his lifetime. But Martin’s most appreciable influence was not on the realms of painting and printmaking but on cinema, particularly the early Hollywood film epics of such directors as DW Griffith and Cecil B DeMille.

Peter Raissis, Prints & drawings Europe 1500–1900, 2014

-

Exhibition history

Shown in 5 exhibitions

Purchases and Acquisitions for 1960, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 22 Mar 1961–23 Apr 1961

Dreams and realities: Victorian works on paper, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 07 Aug 1993–24 Oct 1993

Queens & Sirens: archaeology in 19th century art and design, Geelong Gallery, Geelong, 26 Sep 1998–01 Nov 1998

Printmaking in the age of Romanticism, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 06 Aug 2009–25 Oct 2009

European prints and drawings 1500-1900, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 30 Aug 2014–02 Nov 2014

-

Bibliography

Referenced in 4 publications

-

Michael Campbell, John Martin: visionary printmaker, York, 1992, pp 102-03. CW82

-

Renée Free and Rose Peel, Dreams and realities: Victorian works on paper, Sydney, 1993, 1 (illus.), 10. no catalogue numbers

-

Martin Myrone, John Martin: Apocalypse, London, 2011, pp 130-32. no 58

-

Peter Raissis, Prints & drawings Europe 1500-1900, Sydney, 2014, p 126, coll illus p 127.

-