Title

Self portrait (Non-objective composition)

1984

Artist

-

Details

- Date

- 1984

- Media category

- Installation

- Materials used

- enamel, synthetic polymer paint on hardboard and plywood [8 panels], 2 scythes, sickle

- Dimensions

-

Installation dimensions variable according to room size

:

a - small brown with scythe located on wall, right side of work, 83 x 60.5 x 0.5 cm, wood panel

b - scythe, 147 x 69 x 26 cm, scythe

c - small plywood with brown cross, 83 x 60.5 x 1 cm

d - large brown, 172 x 112 x 0.5 cm

e - small brown with white cross, 83 x 60.5 x 0.5 cm

f - large plywood with white cross and scythe attached to right front of work, 172 x 118 x 27 cm, overall

f - large plywood with white cross and scythe attached to right front of work, 172 x 118 x 26 cm, wood panel

g - scythe, 147 x 69 x 26 cm, scythe

h - small white with brown cross, 83 x 60.5 x 0.5 cm

i - large plywood with white cross, 172 x 118 x 0.5 cm

j - small white with white cross and sickle attached to centre front of work, 83 x 60.5 x 3.5 cm, overall

j - small white with white cross and sickle attached to centre front of work, 83 x 60.5 x 0.5 cm, wood panel

k - sickle, 41 x 12 x 3 cm, sickle

- Signature & date

Not signed. Not dated.

- Credit

- Moët & Chandon Art Acquisition Fund 1988

- Location

- Not on display

- Accession number

- 8.1988.a-k

- Copyright

- © Estate of John Nixon

- Artist information

-

John Nixon

Works in the collection

- Share

-

-

About

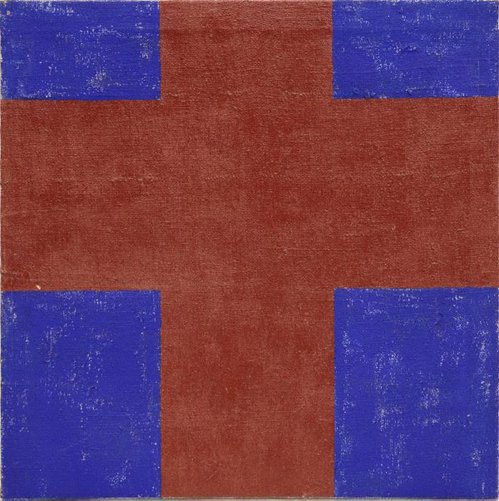

John Nixon’s ‘Self-portrait (non-objective composition)’ is a complex work in terms of its installation format and its title, both of which refer to other paintings. It is made up of eight oval-shaped, painted panels. A scythe is attached to one panel; opposite, across the room, another panel bears a sickle. The installation is arranged so that the relationship between the work and the viewer, and among the parts of the work itself, is understood as collaborative. Nixon had previously displayed works with a common aesthetic together as installations, as well as multipart works conceived as installations from the start. These responded to the influence of minimal art both in the use of basic forms and the use of space as theatre.

The title of this work is as much a standard for Nixon as his motifs and has been used for a number of other works with minor variations. It could be understood that his art is a reflection of himself and works like these might be considered as an extended autobiography. The cross exists as a stand-in for the artist (as it does for Christ), a signature in effect, punning on the ‘x’ of the illiterate. His use of a cross is also a reference to pioneer abstractionist Kasimir Malevich, whom Nixon greatly admired (Nixon’s installations of paintings with squares and crosses echo the reproductions of Malevich’s exhibitions of suprematist paintings), such as ‘Black and orange cross’ 1992 (AGNSW collection).

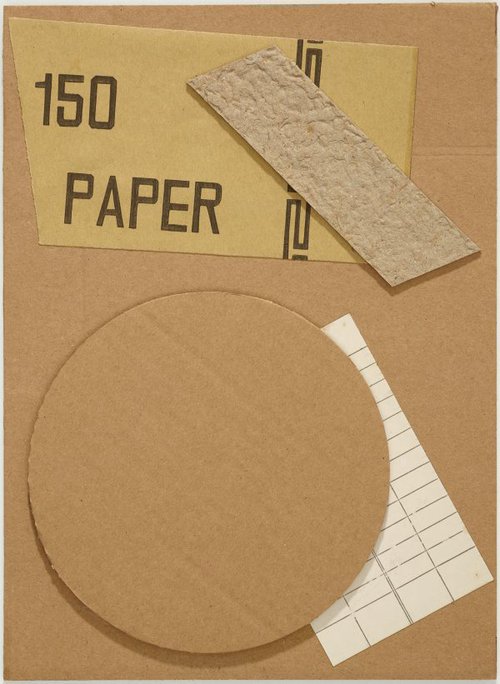

Nixon reuses the cross, square and circle relentlessly, giving his work a serial quality and denaturing the forms to virtually the status of a logo. This in turn allows his materials to assume greater importance. He links the traditional use of artists’ oil paint to illusion and therefore prefers commonplace, ‘honest’ materials. Guided by this logic Nixon paints with house paint straight from the tin and, in a number of the panels in ‘Self-portrait (non-objective composition)’, he has left the surface unprimed to expose the plywood support.

While Nixon claims to include only ordinary, ‘banal’ objects in his work (potatoes, crates, cupboards, apples, etc), the two implements used here are obsolete and romantic reminders of Australia’s pre-industrial culture. The grain cutting tools retain great symbolic value and were used, like the cross, to represent death and life, but more usually, labour.1 Artists of the Russian avant-garde (including Malevich) depicted peasants with scythes and sickles. They were also among the first artists to affix three-dimensional objects to their canvases.2

1. The best-known example of the sickle as a symbol of honest work in the 20th century is the emblem adopted by the Communist party in Russia in the 1920s to represent a combination of agricultural and industrial labour, the crossed hammer and sickle.

2. For example, Vladimir Tatlin included a carpenter’s square in one sculpture, Alexander Rodchenko attached a brick to a painting and Ivan Puni attached a hammer to one work and a plate to another.© Art Gallery of New South Wales Contemporary Collection Handbook, 2006

-

Exhibition history

Shown in 1 exhibition

The Australian Bicentennial Perspecta, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 14 Oct 1987–29 Nov 1987

The Australian Bicentennial Perspecta, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 05 Mar 1988–17 Apr 1988

The Australian Bicentennial Perspecta, Frankfurt Kunstverein, Frankfurt am Main, Sep 1988–Oct 1988

The Australian Bicentennial Perspecta, Wurttembergische Kunstverein, Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Mar 1989–Apr 1989

-

Bibliography

Referenced in 4 publications

-

Anthony Bond and Victoria Lynn, AGNSW Collections, 'Contemporary Practice - Here, There, Everywhere ...', pg. 229-285, Sydney, 1994, 259 (colour illus.).

-

Anthony Bond OAM (Editor), The Australian Bicentennial Perspecta, 'Catalogue', p1-2, Sydney, 1987, 1, 62 (colour illus.).

-

Michael Desmond, Contemporary: Art Gallery of New South Wales Contemporary Collection, 'Abstraction', pg.16-59, Sydney, 2006, 48 (colour illus.).

-

Janet Shanks and John Nixon, John Nixon tableaux, 'John Nixon tableaux: bromide photographs of various exhibitions 1986-1991', Geelong, 1991, n.pag. (illus.). photograph no. 3, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1991

-