-

Details

- Date

- 1989

- Media category

- Installation

- Materials used

- terracotta

- Dimensions

-

23.0 x 1140.0 x 1050.0 cm

:

1-1100 - 1100 clay figures, 23 cm, approx height (each figure)

- Signature & date

Not signed. Not dated.

- Credit

- Mervyn Horton Bequest Fund 1993

- Location

- Not on display

- Accession number

- 314.1993

- Copyright

- © Antony Gormley

- Artist information

-

Antony Gormley

Works in the collection

- Share

-

-

About

The work of Antony Gormley provides us with important insights into some of the most compelling and radical changes that have occurred in modern sculpture and even to major changes in the way we think of representation in art. Artists such as Gormley have quietly shifted the emphasis away from making images of things in the world towards generating experiences of their presence. These experiences may or may not involve images of the things themselves and may simply provide us with a trace or residue of the thing. Minimalism may have provided a conceptual platform for the idea of material that creates its own presence however a younger generation have turned Minimalism's literalism up side down by mining this presence for its affective and metaphorical potential.

Two outstanding effects of this shift that further undermine the nature of autonomy of the artwork are incorporation of site into the material meaning of the work and openness between the artwork and its active beholder. While modern market conditions might seem to dictate portable and self-sufficient objects, artists working with three dimensions have apparently perversely moved in the opposite direction towards site specificity.

The other important shift has been away from completely autonomous art objects whose meaning is supposedly inherent in their form and therefore closed to continuing imaginative work, towards an art that finds its completion in the experiencing mind and body of the viewer. The work of Antony Gormley dramatically embodies these changes.

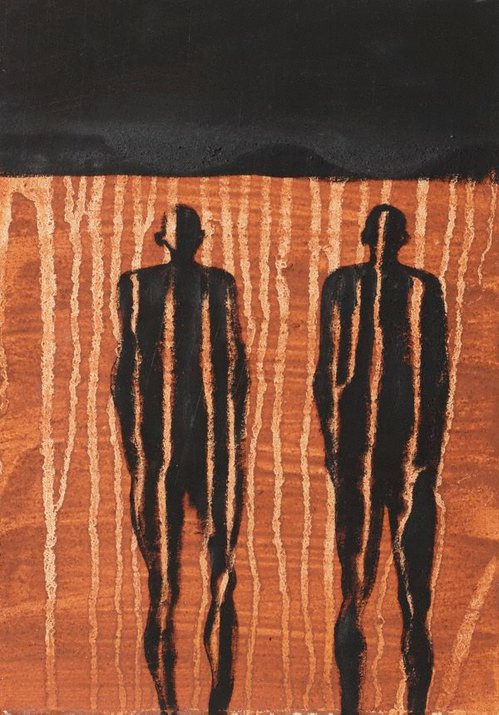

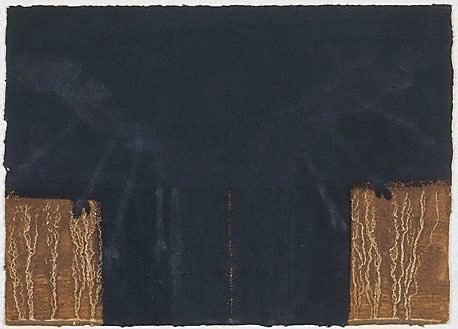

In 1989 Gormley came to Sydney to install 'Field for the Art Gallery of New South Wales' here at the AGNSW and to locate a reciprocal work in the desert, 'Room for the great Australian desert'. He had asked for a site with 360 degrees of uninterrupted flat horizon and red dust underfoot. I located a spot where I knew that the clay pans were extensive and the horizon was terrifyingly flat and low. Standing up there you are the highest object this side of the horizon. It is a vertiginous experience as if you could easily fall from the spinning globe. It was while camping out in this place that Gormley talked to me about Hiedegger and the phenomenological problem of consciousness that always rests so lightly upon the material world out of which it has arisen and yet is always constructed as it's other. There could be no more dramatic and appropriate place for such speculations and for an artwork that embodied them.

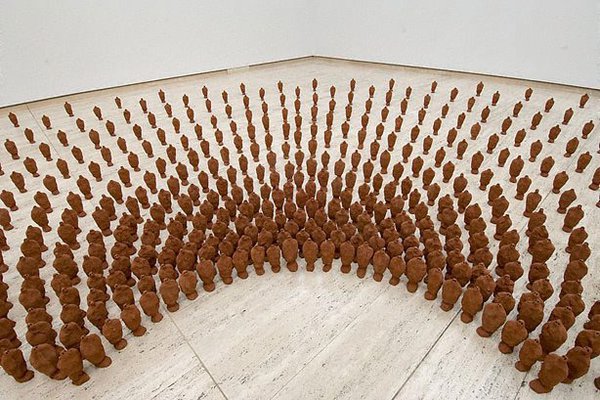

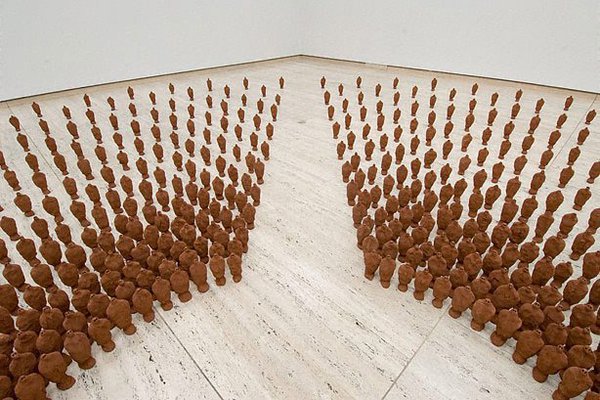

The work Gormley made for the AGNSW is a field of 1,100 little clay figures made from the red bull dust of the centre. The figures are arranged in two hemispheres mimicking the plan of the brain. There is a pathway down the middle to a central lobe where you stand. From this vantage point you become aware that all the figures have eyes that are focused directly on you. I immediately responded to this mass gaze with guilt felt on behalf of mankind that has so badly bruised the land out of which it arose. Others claim to feel godlike. Perhaps both are appropriate; to judge is to be judged after all.

Back in the desert Gormley positioned a concrete body housing. It was designed to exactly house his own body within its cubic form. The figure has a powerful presence in the land even though there is no one to see it. The station manager tells me he has seen it from the air but not visited the site. What Gormley anticipates is that creatures of the desert, spiders, crickets and lizards will have reanimated the hollow form. He has made a number of these architectural suits since then, some of them designed to precisely fit the individual measurements of members of a community. With this and other works like it Gormley has shifted from the singularity of the artist's figure to a position that bears witness to a collective body.

When camping out in the desert one comes across places that feel comfortable and welcoming. This is not to do with any known human history and only in part due to topographical and climatic features. An outcrop of rock can have caves on either side and they may be completely different in atmosphere. One side may even be rather terrifying with an atmosphere of foreboding while a few meters away an overhang beckons you inside and provides comfort for the nights sleep. The extraordinary thing about the 'good' cave is that it always has evidence of multiple occupations thousands of years of cricket and bat droppings, kangaroo and other marsupial traces that are completely missing from the 'bad' cave. The Chinese have codified something of this in Feng Shui but all sentient beings seem to have intuitive responses to particular spaces. I suppose the success of Gormley's 'Room for the great Australian desert' might be measured by the number of insects that have chosen to animate its interior.

There is a collaborative aspect to many of Gormley's later works that extends the incorporation of site into an engagement with living culture. Since 1989 he has sought opportunities to work with communities and to make his art about the communal body rather than the unique and isolated body of the artist. In 'Field for the Art Gallery of New South Wales' the one thousand plus small figures were made by local students, multiple hands performing simple actions to form the likeness of a body but equally making a trace of their own hands.

Anthony Bond

-

Exhibition history

Shown in 1 exhibition

A Field for the Art Gallery of New South Wales: A Room for the Great Australian Desert, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 02 Nov 1989–17 Dec 1989

-

Bibliography

Referenced in 4 publications

-

George Alexander, Look, 'Antony Gormley's vision: the body as a place of memory and transformation', pg.16, Sydney, Apr 2006, 16 (colour illus.).

-

Anthony Bond OAM, Antony Gormley: a field for the Art Gallery of New South Wales, a room for the great Australian desert, Sydney, 1989, (illus.).

-

Natasha Bullock, Contemporary: Art Gallery of New South Wales Contemporary Collection, 'Landscape, mapping, nature', pg.290-331, Sydney, 2006, 308-309 (colour illus.), 431. illustration on pg.309 is a detail

-

John McDonald, The Sydney Morning Herald, 'Sumptuous commodities', pg.93, Sydney, 18 Nov 1989, 93 (illus.).

-